Does your career in BIM and digital construction satisfy you? Does your pay cheque reflect the seniority of your role? If your answer to either of those questions is ‘no’, then you’re not alone.

That’s the immediate conclusion to be drawn from reading the first Women in BIM Digital Construction Global Work Survey in full. Earlier this summer, co-author and principal lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire, Dr Jenni Barrett, presented the highlights at the Women in BIM London conference. The key finding at that stage was that a job title with ‘digital’ in it offers a better salary than one with ‘BIM’ in it. Now that the survey has been published, its full findings can be reviewed.

First, the context. The survey generated 461 responses from 47 countries: 300 of those responses were from women and 100 from men. The geographic analysis shows that 21% came from the UK, 20% from East Asia, 17% from Australia and New Zealand, 15% from North America, 12% from Europe and 8% from South America.

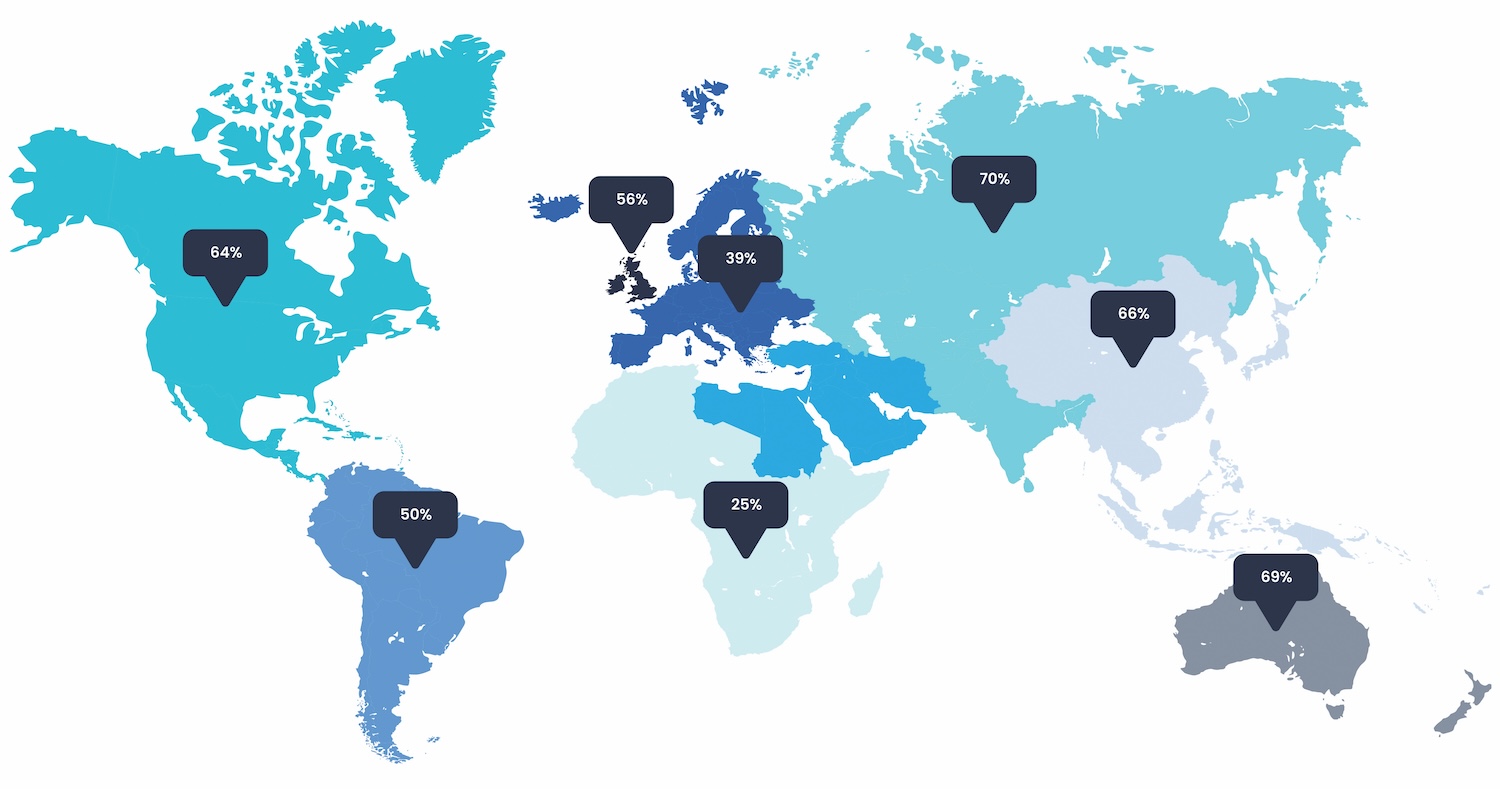

The good news is that, in most regions, the majority of respondents were positive about their career: two-thirds or more of those in Central and South Asia, East Asia, Australia and New Zealand, and North America were positive, as the graphic below illustrates.

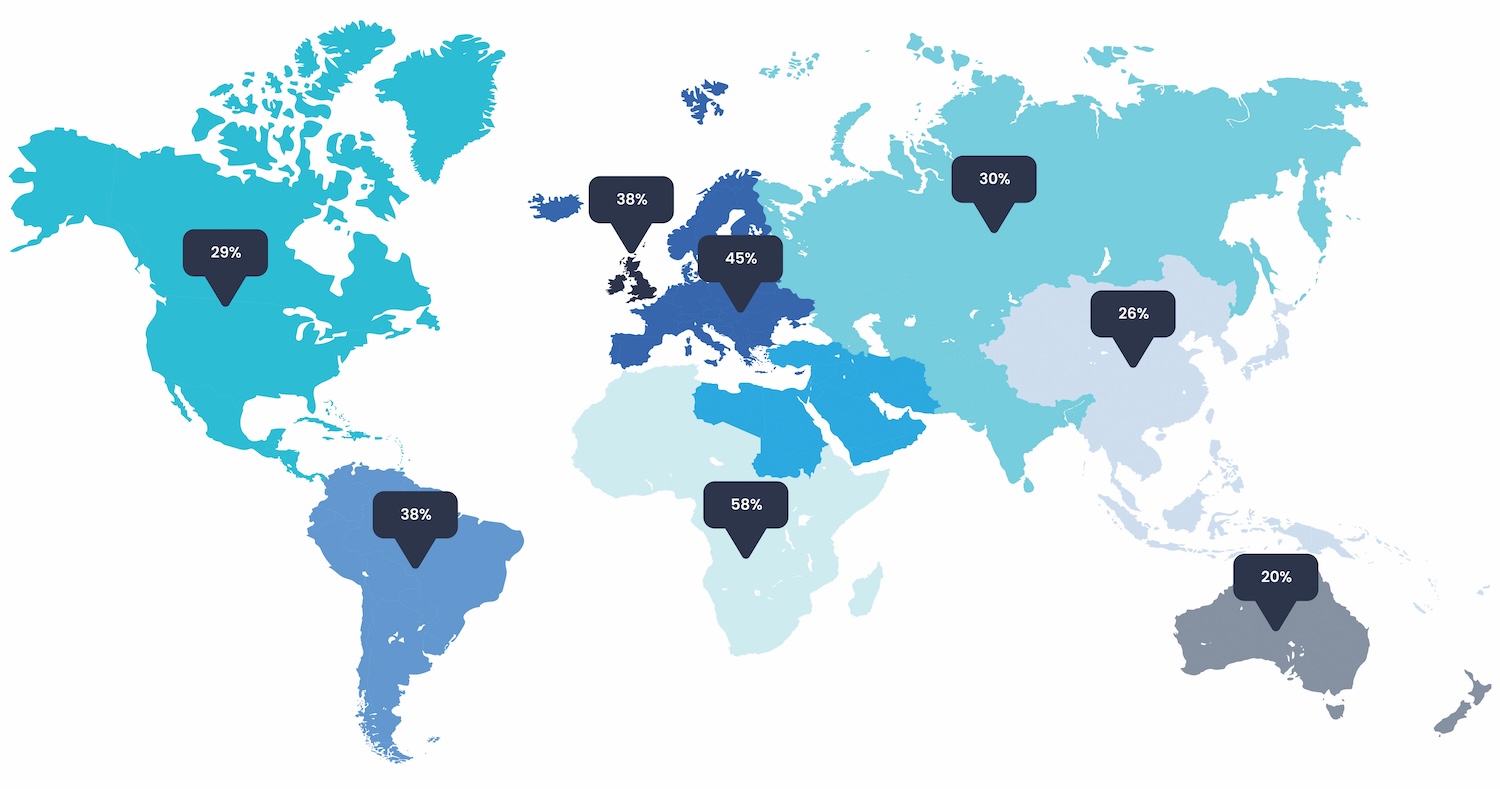

However, a majority of those working in Africa felt negatively about their careers, followed by nearly half of those in Europe and more than a third in the UK and South America, as the next graphic reveals.

Diverse roles bring confusion

Many aspects contribute to this dissatisfaction. As reported after the Women in BIM conference, the 461 survey respondents revealed a total of 87 different job titles, with BIM manager being the most common. Analysis of the tasks allocated to each job title reveals confusion about what a digital role is and what a BIM role is – and thus what salaries such roles should attract.

The training issue

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of respondents reported that they have received training to do their job, with the majority finding that training useful. Of those that received training, 55% reported that this was primarily in relation to the use of specific software packages, Autodesk Revit being the most common. Only 45% indicated that they had received training in relation to their digital or BIM role, or how to ensure effective implementation or compliance.

More than a third (37%) said that they have not received any training to do their job. Many of those who said that they haven’t had any training said they had pursued this themselves via internet search engines, YouTube, or via sharing platforms such as LinkedIn and Lynda. Many had also gained skills by asking colleagues or people in their personal networks questions on areas they were finding difficult.

The survey states: “This suggests that there is a significant training gap and variability in the formal provision of that training that requires attention, especially in a time of rapid digital transformation.”

Dr Barrett tells BIMplus: “The thing that surprised me was the diversity of roles and titles and the lack of clarity in what a digital construction role is. Take an architect: we know what an architect does, we know there are diverse ways of becoming an architect, because it’s an established role. We know the route through education, the first job roles open to you – architectural assistant, architectural technician. We understand that vocabulary, and then we understand architect and partner, director.

“You can see what this means when you enter the profession, you can see that trajectory ahead of you, it’s clear to you. Also, because of the validation criteria for education and the validation criteria for qualification, it’s clear what you need to do to progress and what you need to be good at.

Still finding its identity

“But because BIM is a profession (if we want to call it that) that is still finding its identity, it doesn’t have that common vocabulary. And even when you look at the distinction between BIM and digital, people are being called BIM, yet they’re doing digital, and vice versa, digital people are really just doing BIM. So that causes problems for people, and that really came through in the career satisfaction scoring. People aren’t satisfied because they can’t see where they’re meant to go next.

“If you’re a BIM manager, who are you meant to be? Who are you looking to? What job title are you looking to, saying ‘I want to be that’? Without those clear trajectories and pathways, it’s very dissatisfying for those in the profession.”

Head cook and bottle washer

Dr Barrett continues: “The other thing that surprised me was how much of people’s work, the percentage of their day, is spent training others. That can’t be efficient. As a sector, we’re spending a lot of money and a lot of time training ourselves, and it’s being done in such an ill-defined way, and we need more coordination on that.

Fight for your rights

Of the anomaly of no gender pay gap in North America, Dr Barrett said: “The story that was coming across [from US-based respondents] was that there isn’t a gender pay gap, rather women are having to fight really hard [to get equal pay]. That fight has become normalised, and that’s what’s closed the gender pay gap. But that’s just hiding a gender pay gap: women shouldn’t have to fight to get the same pay as men.”

One respondent in North America said: “I am well-compensated for my work and highly valued for what I bring to the company. I wonder sometimes how my male colleagues are compensated in comparison. I had to be pretty assertive when negotiating my salary.”

“There are some pressured individuals out there who are being given everything to do, from pushing the buttons on Revit to training others and then influencing their senior colleagues to redesign systems and organisational behaviours to fit this sector. And that’s a lot; it’s no wonder career satisfaction scores were lower in some areas.”

And yes, there is a gender pay gap. The survey data indicates a perceptible gender pay gap in the global, digital construction sector. A noticeably higher proportion of men secure the highest salaries compared to women. Nearly a third of men (31%) of men secure salaries in the highest band compared to only 21% of women.

From the data available, the largest pay disparity between women and men existed in South America. In North America there was no disparity, while in the UK and Australia and New Zealand indications are that a gender pay gap exists.

Reviewing gender regarding career satisfaction, the data indicates that men are more likely to feel more positively about their careers than women. Nearly 70% of men feel positive about their careers, whereas just over half of women feel the same. Conversely, only a quarter of men feel negatively about their careers, while the percentage of women exceeds this figure.

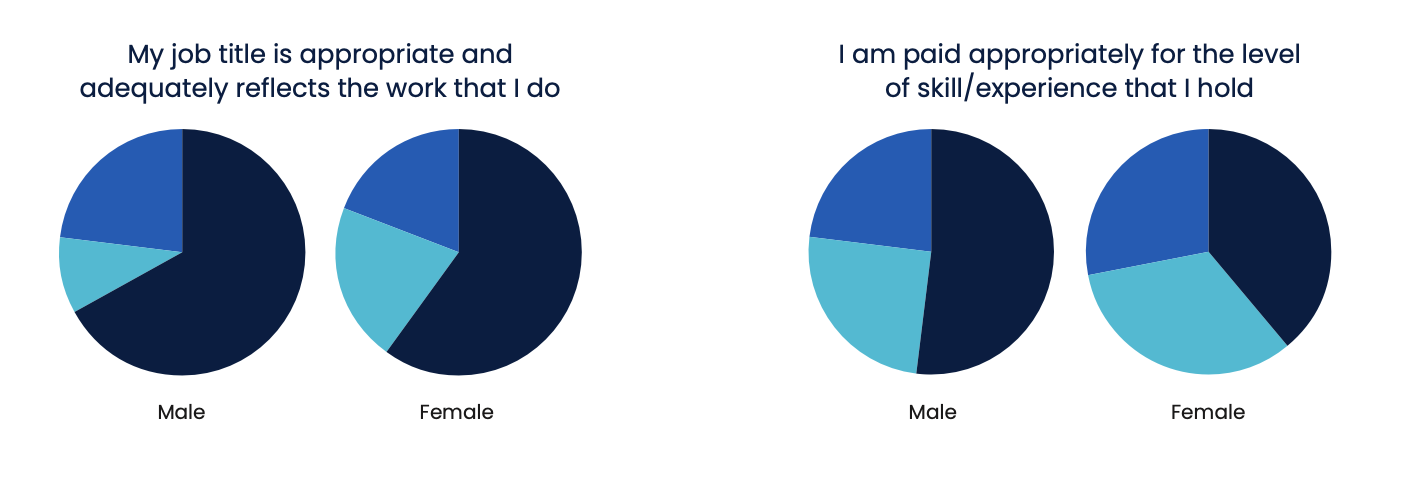

Not paid appropriately

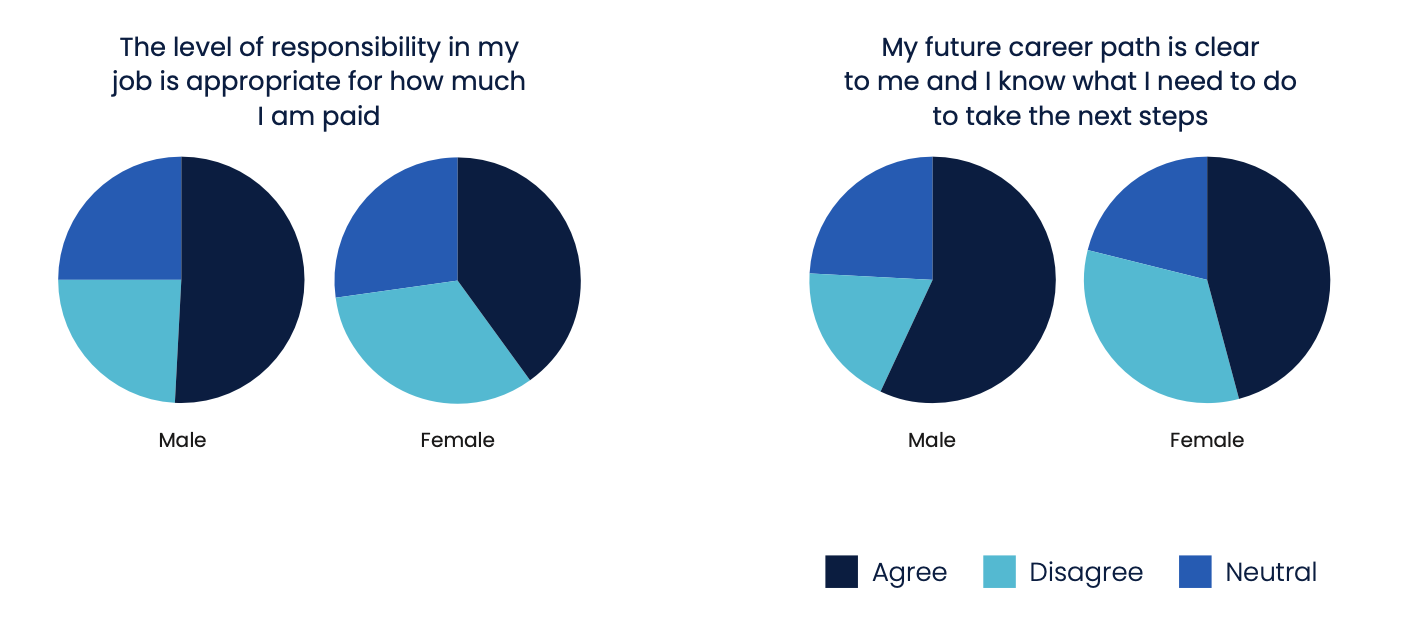

The gender pay disparity may be one factor that leads women to feel less positively about their career in digital construction than men. This can be inferred from the finding that women are less likely to feel that they are paid appropriately for their level of responsibility, skill and experience. Women are also less likely to feel that their job title adequately reflects the work they do, and for them, future career progression is also less clear.

To conclude, BIMplus asked Dr Barrett what someone should do after reading the survey results. She answers emphatically: “If I was a senior manager in a construction organisation, it would remind me that I need to have a look at what the career pathways [for BIM and digital staff] are. If I want to retain these staff, I need to give them satisfaction via a clear pathway for their career development. I need to bring that clarity not just internally, but also outside my organisation.

“As a BIM manager, I would raise the information that the survey highlights with the senior manager and ask them to respond.”

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.