A team led by UCL Consultants has won the £2.7m contract to deliver the National Buildings Database for the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

The National Buildings Database, a carbon Domesday Book if you will, will mark a “step-change in the evidence available for analysis of decarbonisation across the building stock”, according to the Department.

The database will comprise a spatially located geometrical representation of each building, to which will be assigned data on age, construction, internal activities, building services, energy rating and actual energy use. An emphasis will be placed on addressing gaps in understanding of the non-domestic building stock.

The database will enable co-located buildings with similar or complementary demand profiles to be identified, which could support zoning of heat networks, analysing proximity of industrial energy end uses (which present opportunities for district heating networks) and identification of buildings at risk from climate change impacts, through cross-referencing with local-scale climate model outputs.

The database’s scope extends to all types of domestic and non-domestic building, including the following definitions (or ‘activity classes’ as the project team refers to them) of the latter:

- agriculture;

- arts and leisure;

- community;

- defence;

- education;

- emergency services;

- factories;

- health;

- hospitality;

- offices;

- shops;

- sport;

- transport;

- utilities; and

- warehouses.

The database will cover England, Wales, and Scotland. For the moment, data compatibility issues mean that further work is required to cover Northern Ireland in the future. The contract stipulates that the UCL team will need to hand over the database to the government in March 2025.

BIMplus spoke to Paul Ruyssevelt, professor of energy and building performance at UCL, who is leading the 30-strong project team, to find out more.

BIMplus: The database will cover both domestic and non-domestic buildings…

Paul Ruyssevelt: We’re doing non-domestic in detail, but we’re also covering all domestic buildings as well. The reason for doing that is primarily because, in dense urban areas, domestic and non-domestic is actually quite mixed. And you can’t really get a handle on the non-domestic unless you understand where it fits in with domestic. So, things like flats over offices or over shops are quite a significant component. It’s as easy for us to map the whole thing, to be honest. That’s what our systems are designed to do and what we’ve been doing for a number of years.

“It uses, largely, publicly available sources of data, which we bring together in ways that haven’t been done before.”

Tell us how the database works

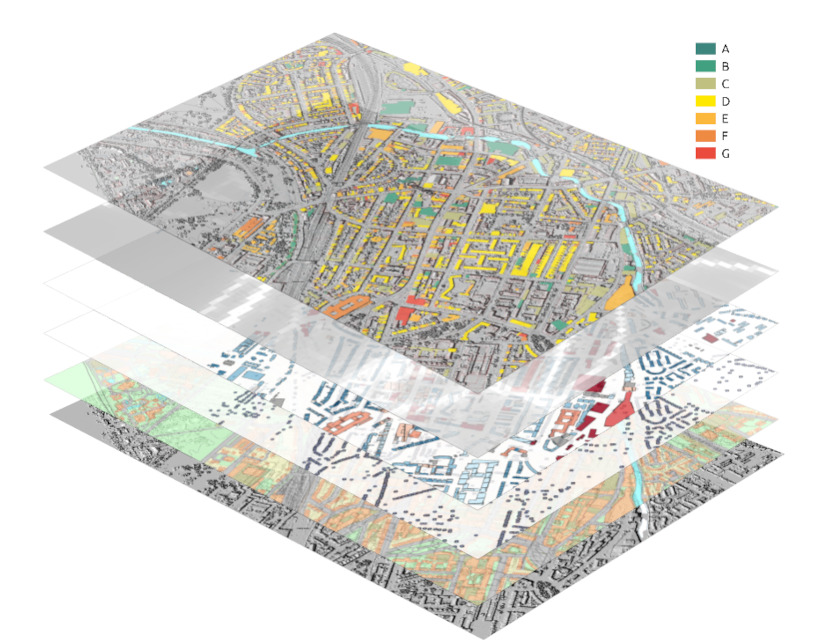

The Building Stock Lab, a team of researchers in the UCL Energy Institute, has been developing something called 3DStock for about eight years now. It builds on a couple of decades of work in the non-domestic building sector, trying to understand the make-up of the stock and how it uses energy. 3DStock is essentially a digital representation of the existing built environment in the UK.

It uses, largely, publicly available sources of data, which we bring together in ways that haven’t been done before. So we bring in things like the Ordnance Survey mapping system, Ordnance Survey Address Base, polygons, building heights. We draw in data from the Valuation Office Agency (VOA), which produces the data for the rating of commercial premises used by HMRC.

The VOA records floor space data by use type, and by floor. So for most non-domestic buildings, they will know how much floor space on the first floor is dedicated to offices, how much is circulation space, how much storage space and so forth. Not all premises are covered in that way.

Some are rated on other factors and floor space data isn’t available. Hospitality is an example, and this led to it being chosen as a good test of the method in the pilot project, which was completed in March, with a report to be published soon. When floor space data isn’t available from the VOA, we can sometimes obtain it from an EPC certificate if there is one available. Access to EPC data provides a rich source of information on other parameters such as building fabric and building services.

What about meter data?

We will pull in the annualised data for every meter in the country. And one of the things that we’ve been able to bring to this project is a mechanism of matching those meters to actual premises, because that’s not a straightforward process – they don’t always come with a very clear address or unique property reference number.

Mixed-use buildings must present a particular challenge?

“I’d like to look at ways of taking key information from BIM models, so that we could make these urban scale models much richer and more accurate.”

The word ‘building’ doesn’t mean very much in non-domestic stock. We refer to premises. These are spaces that are occupied by individual owners or occupiers, and they may be a whole building, or they could be a floor in a building, or they could be a collection of buildings, or a space that extends across the first floor of several buildings.

The only way you can ever get a handle on all of that is by having a three-dimensional model, which is essentially what we’ve got. And the three dimensions for the model come from Environment Agency (EA) data. The EA scans the whole of the country with LiDAR, building up a point cloud that represents the topography and the buildings.

The EA does this primarily because of flooding and flood risk. But the data is publicly available, and we have a mechanism to process it and turn it into three-dimensional representations of buildings, and superimpose those buildings on the polygon footprints from the Ordnance Survey.

We have previously used UKBuildings data from Verisk, to obtain information on construction materials and other building characteristics, and this may be used again for the National Buildings Database.

We don’t have floor layouts. When the VOA data tells us that there’s some office space, some circulation space, and some storage space on the floor of a building, we don’t know where that is, we just know what the floor area is. For most of our purposes, that’s adequate.

Could you use BIM models?

I’m interested to see if we can, over time, take information from BIM models. They can contain masses of information and you could never federate all of that into a model of a city. But I’d like to look at ways of taking key information from BIM models, so that we could make these urban scale models much richer and more accurate.

Security must be a factor?

One thing to stress about all of this is that there is quite a bit of confidential data going into it. So it’s all held in a very secure environment with very strict procedures around who’s able to access it, and where it can be accessed.

What’s the biggest challenge between now and March 2025?

The time! It’s a big job in a fairly short space of time. That said, we’ve got very clear plans of how we’ll go about it.

We’re not just assembling the data, using the various sources mentioned: there is a need to try to calibrate that data, and gain insights to make sure that we have confidence in it. That’s where our partners, Winning Moves and Verco, come in.

“There is a need to try to calibrate that data, and gain insights to make sure that we have confidence in it.”

Winning Moves is a market research organisation that we’ve worked with on a number of projects. They will conduct a large campaign of telephone surveys across these different activity classes. They’ll be looking to understand whether we have the basics right. For example, when we think a premises is a shop, is it a shop or is it a Chinese takeaway? So there’s a first wave of surveys that are just about basic quality assurance of some of the key aspects of the data.

Winning Moves will then follow that up with insight surveys, where we hope to speak to somebody who knows a bit more about the energy use or the building services in any given premises. And we’ll try to gain information on how the building is occupied and operated.

That also gives us some insights into the sorts of mitigation measures that organisations have taken, or are thinking of taking, with their premises.

Verco will conduct a significant number of onsite audits, which aim to test the confidence that can be placed on the EPC data that exists for many non-domestic buildings. They will use the data gathered in the audit to model the building in the way you would for an EPC.

We will then build our own model of each premises in an open-source dynamic simulation method, which we plan to calibrate with half-hourly energy meter data from the site. A comparison of the EPC model and the calibrated model will help us to understand and qualify the EPC data on total energy use and the breakdown between various energy uses, such as heating, lighting, ventilation, and small power.

The results of this comparison will then be applied to each activity class so we can provide a National Buildings Database that contains the most comprehensive and confident analysis of energy use and carbon emissions in the building stock.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.