The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) is already leading some forecasters to predict a startling vision of construction in a generation’s time – where roles traditionally carried out by human beings are instead performed by robots. In the first of our special features Denise Chevin examines which areas of the industry will be most affected.

The rise of AI is the great story of our time. Those who have delved online to ask “Will a robot take my job?” might take comfort that design and construction professions such as architects, quantity surveyors or construction managers are low down on the list of professions likely to be replaced by machines, compiled by scientists from the Martin School at Oxford University in 2015.

But that belies the profound impact experts say artificial intelligence and machine learning will have on the roles that both trades and professionals do in the built environment.

It’s still early days but we’re already seeing a plethora of different prototypes providing glimpses of how design and construction activity might change in the future. There’s software that crunches building codes to generate lots of different design variations, or software that helps construction firms spot safety failures, to the development of self-driving excavators guided by drones.

It won’t happen overnight, but AI is seen as a key ingredient to help the industry boost productivity and potentially provide an answer to the skills gap.

A report from construction firm Mace based on the same Oxford University statistics forecasts that 600,000 trades jobs will disappear by 2040 as construction heads to the so-called fourth technological revolution, which includes AI and the Internet of Things.

The overriding conclusion of members of the CIOB’s Digital Technologies & Asset Management Special Interest Group chaired by David Philp is that momentum is most definitely building for AI in the construction sector and despite a degree of hype, ultimately it would have a profound impact.

“Over the years, AI has undergone several waves of growing and waning interest. Lately, with the surge in applications across a number of domains we are now suddenly waking up to the enormous potentials of automation through AI applications in just about every sector,” commented one member.

Read more AI features

- How ‘learning’ building controls boost energy efficiency

- CIOB Digital Special Interest Group: ‘The potential is enormous’

- Autodesk: ‘There’s no future planning that doesn’t involve AI

AI, of which machine learning is a major branch, represents a fundamentally different approach to software. The machine learns from examples, rather than being explicitly programmed for a particular outcome. It might not be obvious, but it’s already found a place in everyday life, providing an efficient means of searching for images on smart phones purely by typing in the subject, and the emergence of intelligent digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa now capable of holding conversations with humans.

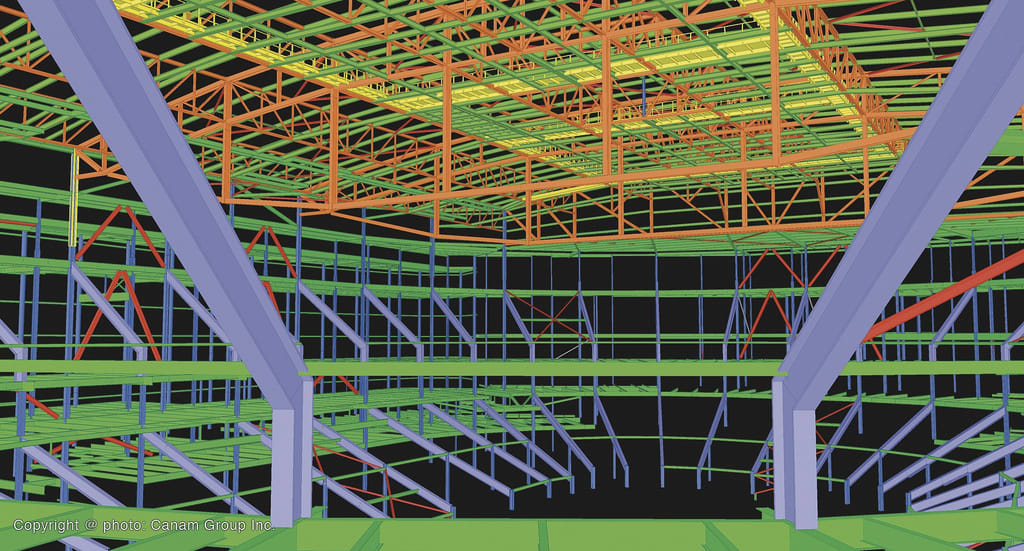

AI has been touted as the next big thing in the past, but the confluence of greater connectivity and availability of huge amounts of data emanating from processes like BIM and sensors, coupled with infinite computing power to recognise patterns in that data, has created a fertile environment in which research and development in AI can thrive, explains Tatjana Dzambazova, AI strategist at Autodesk.

Its first publicly available machine learning-powered tool focused on construction is BIM360 IQ, which uses machine learning to predict and prioritise issues such as subcontractor risk. “It can advise the superintendent [manager] of the performance grades of subcontractors and their historic data in order to make sure they pick the right teams. All this is possible thanks to historic data of over 27 million documented issues from 10 years of BIM field data that were used to ‘train’ the system,” says Dzambazova.

In such a fast-moving world no one can say for sure just how smart machines might become but in the medium-term futurologists developing the technology for the built environment suggest that construction professionals should think of AI not taking their jobs, but augmenting their skills – to provide them with “superpowers” as it were.

“I think history shows that when machines took parts of jobs over they created high level jobs in return,” says Ákos Pfemeter, vice president of marketing at Graphisoft, which has embedded AI into ArchiCAD 21, the latest version of its BIM modelling software.

It includes predictive technology to automate stair design, a complex aspect of projects which has to take on board hundreds of design codes. Pfemeter reiterates the embryonic stage of AI’s use in construction, but highlights the vast potential.

“There are definitely three areas in construction where we can see the most potential. These are building design and analysis; construction technologies; and lastly building operation – arguably the most advanced area of the three,” he says.

But as AI is picked up on the sector’s radar, expect it to generate more than a few ripples. “Yes, automation technologies exist and are being used – particularly with regard to parametric design [a process based on algorithms] – but they are not widespread,” says Phil Langley, director at Bryden Wood.

“AI has not yet ‘landed’ in the design and construction industry, not just because of the technological maturity, or the skills gap that clearly exists, but also because the industry has not yet confronted the consequences – in terms of skills, labour, business models etc – or the shockwaves that would be produced by the widespread adoption of AI.”

How robots could make construction more productive

Komatsu is aiming to create machines with embedded AI

The addition of AI and machine learning to robots and image recognition software will be increasingly harnessed to improve construction processes and productivity.

At the heart of a number of these developments is the graphics hardware giant Nvidia, which has teamed up with a number of construction companies to supply its chip with AI capabilities. One of these is Komatsu, Japan’s largest maker of construction machinery, which is aiming to create a generation of products with embedded artificial intelligence as a step towards unmanned equipment.

Nvidia will also supply AI chips that allow Komatsu machinery to “see” the site around them, and react automatically to developments as they take place. They will be complemented by drones equipped with similar graphics processors.

Rian Whitton, an analyst with international consultant ABI Research, highlights the potential of smart drones. “Among the most obvious tasks affected by AI in construction will be surveying, monitoring and inspection, in large part because commercial-grade unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV)s are AI-capable,” he says.

“In the case of surveying, drones can provide aerial imaging cover at a reduced price, and can minimise the time needed for surveying from days to hours. For the most part, UAVs collect data from a site, upload it to a cloud, after which bespoke software garners insights from the data. Having on-device machine-learning capability could provide that service in real-time, allowing managers and operators to understand and react immediately to developments on the ground.

Whitton adds: “Expand that to multiple platforms that fly, land, dock and recharge autonomously, and you have a much more comprehensive understanding of the project. This information will allow for much better allocation of resources, and will help managers find the most efficient routes to move material through the construction site. Beyond maintenance, having real-time analysis of a site will help contractors at the surveying, estimating and planning phases as well.”

So how far are we down this road? “Not very,” says Whitton. “Commercial drone opportunities have only begun to gain momentum in construction, and with them comes a range of AI/ML solutions. I would suggest some of the technologies being talked about will reach maturity within three years.”

As well as “vision” learning systems, the development of robots equipped with machine learning is also seen as having huge potential to increase productivity and quality. Whereas traditional robots had to be specifically programmed to do a limited number of tasks in a specified environment, the new generation do not have to be so rigid and pre-defined, explains Autodesk’s Tatjana Dzambazova.

“In our robotic lab in San Francisco, we are currently piloting a construction site robot that can install glass façade panels from the interior of a building, a task that is usually quite laborious and dangerous, especially when installing on upper floors,” she explains.

“We initially train the robot by having a human guide its movements via a virtual reality set. Through this training the robot learns the nature of the task to find a glass panel in a certain area, to lift it in a certain way and place it in a recognisable location.”

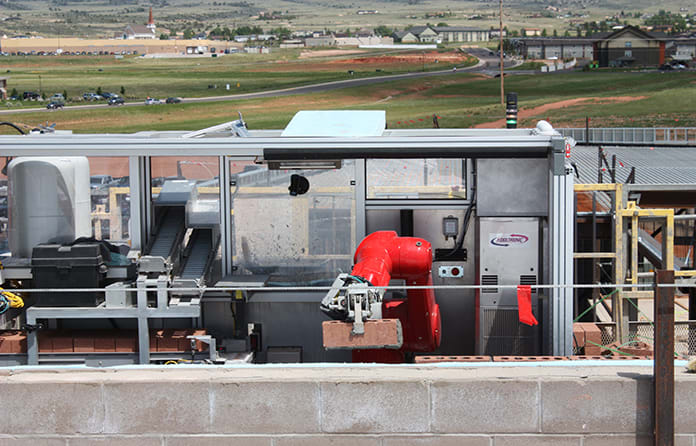

Smart robots are now available for bricklaying

Smart robots are springing up to do a number of tasks – from installing rebar to bricklaying. One such model, called Hadrian, can lay 1,000 bricks an hour, working day and night, and could theoretically build as many as 150 homes a year. However, there is also debate as to where their future lies.

Nick Leach, strategic BIM manager at Sir Robert McAlpine, says: “The real immediate potential I see taking an effect on construction in the short term is around the automation with computing/machine learning – where utilisation of data to analyse not just design but site-based tasks and management activities will improve how projects are delivered, raising the bar further in the quality and safety of our construction sites.”

He cites image recognition systems with multiple uses as an example of technology that will gain momentum.

“I would say it’s an exciting time. Companies are starting to realise the potential, but with developments happening on so many fronts it can be a minefield for organisations in deciding on the right way to go.”

Graphisoft’s Ákos Pfemeter also believes the future is not about building machines that replace what humans do, such as building brick walls, but more about developing smart factory-based machines. “The size of bricks has not changed for 500 years; they are optimised for human labour. It doesn’t make any sense to introduce a machine to replace directly how a human would do it,” he says.

Paul Cook, head of technology at ISG Technology Solutions, also points to another factor in determining the impact of the new technology.

“Artificial intelligence will continue to evolve and refine the technology used in construction and buildings’ software, as it is doing so in everyday aspects of our lives,” he says. “But I don’t believe these advancements will lead to huge strides in the design and performance of buildings and the construction process, unless we fundamentally change the very design approach that is used – a shift from designing and procuring in silos to implementation via a master systems architect.

“Without this radical transition, technology such as AI, VR and AR will not reach its optimum potential, because the platforms and eco-systems they use are not seamlessly integrated.”

How AI and computational design is changing to the role of the designer

Using computers to automate repetitive aspects of design is already used in engineering and to a lesser degree architecture, and is “already having an impact on the way we structure teams and use manpower”, says Carolina Bartram, an associate director at Arup.

As software packages automate designs of components like beams and floor slabs, fewer junior engineers are needed to do the traditional detailed design work and more time is spent looking at iterations and improving the design, she adds.

Bartram says the front end and concept design will continue to be done manually, for example, looking at the overall design of the structure, deciding whether the structure will have load bearing walls and similar decisions.

“Machines might generate different options, but humans are still needed to make the choice of which to use and it’s likely to remain that way for the future. With engineering there is never just one answer – there are always multiple answers,” she reasons. Arup is involved in using AI to improve energy efficiency in galleries.

Phil Langley, director of integrated design and operations consultancy Bryden Wood, agrees. “AI/ automation significantly changes the role of the designer from the ‘author of the outcome’, to the ‘author of the system’ that generates the outcome. This is obviously a new approach and the conventional skills will become less relevant – the race will be on for the existing design community to develop the necessary skills to respond to this technological challenge.

“AI/ automation will mean fewer people doing traditional design tasks – and focusing human knowledge and expertise in the areas where they can add value.”

Graphisoft’s Ákos Pfemeter thinks similarly. “Machines won’t take over from architects any time soon in terms of aesthetics. Someone still needs to make decisions and only humans can do that.”

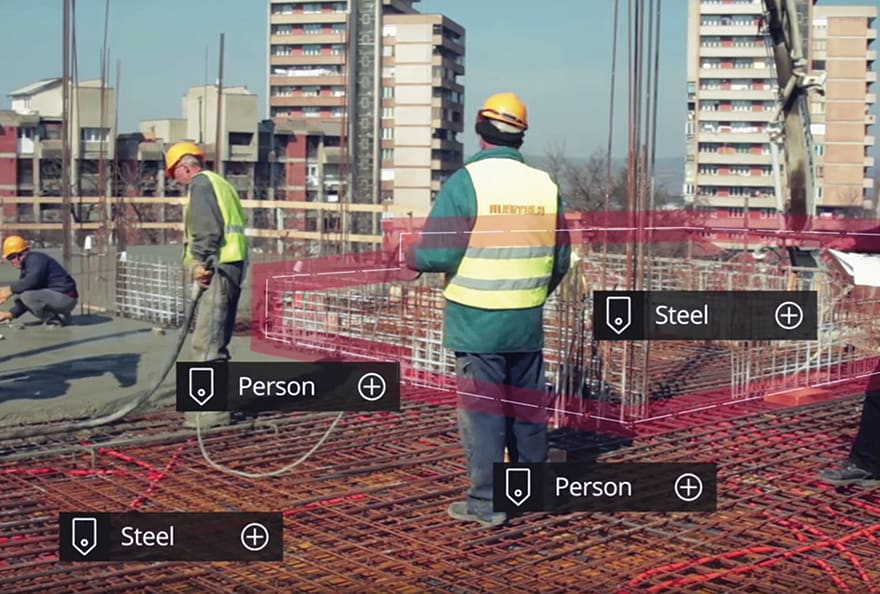

How AI can boost site safety

In another application of Nvidia chip technology, Boston-based Smartvid.io has developed software that uses artificial intelligence to help spot health and safety breaches on site. It is being trialled by a number of contractors in the US, including Skanska. Josh Kanner, founder of the company, says that he is also in talks with a number of major contractors in the UK.

Smartvid.io automatically tags files showing people, hardhats, ladders, and now gloves, and other things relevant to safety. It is then easy to search across projects for relevant tags to review already-curated photos and videos and marks any potential risks.

Pictures can be uploaded from any device or source and there is auto-sync with software such as Procore and Autodesk’s BIM 360 Field, the construction management software Skanska is using in its pilot schemes with the company. Skanska says that it plans to use the software more widely to “help teams get broader safety coverage of its projects”.

The philosophy behind the new product is to supplement the work of the site safety team, not replace it. Says Kanner: “Safety teams are spread too thinly to be proactive on all sites and it’s not uncommon to have one safety manager on 5-10 active projects. I think it’s a common theme to equate AI with the replacement of people. But what we’re doing augments what workers to do by giving them ‘superpowers’. Without this technology it would take too long and it just wouldn’t happen.”

A further stage of Smartvid.io development is analysing site activity to spot defects. UK engineer Arup has been using the technology to spot defects in tunnels.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Hi,

“… There’s software that crunches building codes to generate lots of different design variations … ” – Care to share source?

So many ideas from so many innovative people! Some on point, some completely off it too.

AI has no boundaries. At a high level, show it what to do and teach it how to reason about its decisions.

An AI generally encapsulates features that can be applied to a single purpose. To explain, I like to use the analogy of teaching a baby boy what a cat is. Children are inquisitive by nature and fortunately, they ask questions like what? why? who? (Our machinic counterparts do not do this. Fortunately AI frameworks enable this) When the boy sees a cat for the first time, he asks what it is. It is our role to educate “that is a cat”, the child understands and next time he sees a cat, he exclaims “cat”! However, the child will have incomplete understanding of the full range of animals, so he will not be able to identify an iguana for instance (not sure I would either :)) but the same rules apply to training a machine. You can show the computer a cat (train it), then provide it many pictures and it will be able to select the cat.

Going back to Pfemeter’s point about aesthetics, we need to show it what constitutes aesthetics. How we do that? Take for example, a facade, we can create a generator to provide the human with options, the human chooses, and teaches the machine what is good aesthetics.

There are so many machine learning techniques that can be applied at all stages of the design process. Carolina Bartram touches upon the potential but fails to understand that the concept of replacing junior architects as described by creating programs to replicate their actions will apply the whole way up to the traditional senior architect roles. Those generative scripts she speaks about, can be run at scale in a data centre and orchestrated in a way so that a designer can provide the parameters typically established at the brief stage and solutions generated.

The future: An architect will be profiled by their machinic counterparts. Some future startup (tbc) will interpret design rules that generate and analyze, feedback to the designer and they will, through some thin client “like or dislike” the design. This human:machine symbiosis will ensure that the AI that they are training will be more effective next time!

We are already seeing apps like smartvid.io etc target parts of the asset lifecycle but there is a long way to go – but lets not race ahead, one AI application at a time!

My question is, why would a client use an architect to choose now? I mean, I don’t need a professional to choose the kind of shoes I like – Same for a building.

Great post Denise! Loving the extra exposure on construction ai – best Gari