Structural steel has used digital technology and 3D modelling far longer than most parts of the construction supply chain – so does that mean it’s ahead of the game with BIM Level 2 adoption? Neil Gerrard investigates.

If there’s one corner of construction where the uptake of BIM ought to be higher than anywhere else, then it’s the structural steelwork sector.

Construction industry adoption of BIM Level 2 is still sluggish, as this year’s CM BIM survey showed (April 2018 issue), despite the government mandate for its use on public projects kicking in two years ago.

But steel has had a head start. 3D modelling has been common for at least the last 20 years because steelwork firms were early users of CAD technology for designing and fabricating. So does that mean the sector is now leading the way on BIM level 2 uptake?

Simon Bingham, chairman of Nottingham-based structural steelwork contractor Caunton Engineering, says his firm is well versed in the use of BIM.

“We were doing 3D modelling, which essentially is what they now call BIM, with steel back in 1986,” he says. “But then it wasn’t until 1999 when we did our first job where we engaged in interoperability, where we were collating other people’s data into a model to make sure it all worked.”

The advantages to using BIM Level 2 and above are clear to Bingham, albeit difficult to quantify. “Putting numbers on it would be very difficult but BIM Level 2 would allow us to make both programme and cost savings,” he says.

Unfortunately, though, there is one problem. “We can work to BIM Level 2, if we had anyone to work with us,” Bingham says. He says Caunton has worked on very few projects that can be truly labelled as meeting the Level 2 standard.

Bingham sees main contractors often starting off using standardised forms of contract on BIM projects but changing them “to their own ends”.

“What we should have is a standard approach. We have got naming conventions, we have got standards to work to, we have a digital code of works. But it is largely just being cherrypicked and the difficult bits ignored,” Bingham says.

Image: Thijs Wolzak

MX3D, Autodesk Heijmans and Joris Laarman are working on a 3D-printed stainless steel bridge to be installed in Amsterdam this year

“Coordination at the front end of the job is hard work. It requires dedication, collaboration, and skilled people. A lot of contractors have a look at it, but fall over because it looks like hard work because their own procurement models are bust, and they don’t have the right people in place at the right time to make it work.

“So they call in a third party to come and digitise it once it has been built and then claim it was built to BIM Level 2,” Bingham adds.

That’s not a way of working that Dr David Moore, director of engineering at the British Constructional Steelwork Association (BCSA), recognises.

“I haven’t come across that. They should be doing it properly if they are doing it at all,” he says.

According to Moore, there is considerable interest in BIM from the BCSA’s members. He has recently held eight courses in Level 2 BIM, training up a total of around 160 people.

Further savings to be made

Because steelwork contractors already generally use 3D modelling, Moore says the savings his members can make through BIM Level 2 aren’t necessarily as great as for other parts of the construction supply chain. But there are savings to be made, he adds, particularly in terms of not having to key in the 3D model itself, instead accepting one from the consultant or the main contractor.

The BCSA has set up the Steel Construction BIM Charter, which enables companies to be certified against the requirements of PAS 91: 2013 (the standard relating to construction pre-qualification questionnaires) and PAS 1192-2:2013 (which provides the framework for collaborative working and information management in a BIM Level 2 environment).

“By signing up to the BIM charter, you are demonstrating to the client and main contractor that you are BIM Level 2 compliant and that avoids some of the issues associated with pre-qualification,” Moore explains.

So far, 25% of the BCSA’s membership is signed up – including many of the bigger contractors, meaning a larger share of the steelwork market is signed up than the figure suggests.

BIM helped speed Mott MacDonald’s work on the Jakarta velodrome, where the roof made use of a steel frame

Nonetheless, Moore recognises that there are obstacles to adopting BIM. One of the main ones is the issue of liability. He explains: “A lot of my members ask if they should trust the model they get from the main contractor.

“Most consultants I speak to say they guarantee that when the model leaves them it is correct, which it might well be, but it goes through a number of software iterations before it reaches the steelwork contractor. That’s why we say to our members that before they start a project they should do a trial run.”

The other potential obstacle, Moore finds, is that some contractors struggle to understand how a model works unless they have keyed it in themselves, although younger generations tend to be able to get to grips with 3D modelling from the start, he says.

Finally, language can be a problem. Moore says: “When we start talking about BIM it contains its own definitions and a language all of its own.

“Terms like ‘levels of maturity’ and ‘federated models’ aren’t words that engineers use in their everyday lives.”

One consulting engineer who is familiar with these terms is Matthew Pearce, principal structural engineer at Mott MacDonald. Part of the London structures team, Pearce has experience of BIM in the UK and overseas, and estimates that 80-90% of the projects he works on are BIM Level 2 or above.

Uptake has increased gradually over the past few years, he believes.

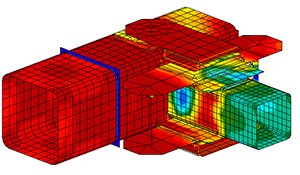

Detail of steel construction joint in BIM

“The real benefits are when everyone is using it, from the architect to the MEP engineer,” Pearce says. “If they aren’t using it then it can really hinder the process, but if they are then it really helps with coordination.”

He cites the example of how BIM sped up the design and construction of the Jakarta International Velodrome in Indonesia, an enclosed arena where the roof was constructed using a steel frame.

Pearce says: “I worked on the London Velodrome and that took about 12-18 months to do the design. On Jakarta we only had half the time, so because it was design and build we were working directly with the contractor to build the model, almost at concept stage, and then add more detail as we went.

“It took about six months to do it from start to finish. If everyone is on board with it then use of BIM saves time. But it is only as good as its weakest team member.”

Pearce thinks that BIM adoption may be lower in the UK than in some other areas of the world and says having buy-in from the principal contractor is key.

Nonetheless, he has seen the use of 4D and 5D BIM in the UK, notably in the case of the £77m Casement Park stadium in Belfast, now going through planning.

“We used 4D to show the construction planning because it is quite a constrained site, and then we used 5D because our cost team did the costing for the project, so we were able to integrate the cost information into the Revit model and then that was used to produce the bill of quantities,” he explains.

Pearce sees the main obstacle to BIM adoption as accessibility – with clients and non-technical design team members not necessarily familiar with the specialist software required.

“I think one way to improve it, and it’s the way it’s going, is for it to become more web-based,” Pearce says.

“If you can interact with models using a web browser, spin it around and even start to modify it, then that definitely helps with accessibility.”

Bingham, despite his scepticism about BIM adoption so far, is hopeful that technology can provide the answer.

“Construction has been focused on putting information into these models,” he says. “You start out with a skeleton and you enrich the dataset as the project progresses. But there is technology now such as point cloud 3D laser scanning that can create data automatically.”

Moore sees the potential for technologies like augmented reality (see box), although he says the industry still needs to understand how best to exploit it. Some BCSA members are beginning to use robotics in their workshops, he says – and he believes applications for 3D printing are on the horizon.

He is excited about plans to 3D print a stainless steel bridge in Amsterdam, a project involving Dutch robotics startup MX3D with Autodesk, construction firm Heijmans and designer Joris Laarman. It is to be installed in late 2018 over the Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal.

“These technologies are changing rapidly and we need to see how we can use them in everyday steelwork construction,” Moore says.

Using VR and AR with steel

Construction is increasingly turning to virtual reality and augmented reality (VR and AR) to help bring BIM to life.

Positioning specialist Trimble Solutions is using Microsoft’s lightweight HoloLens headset for this purpose, and has recently combined the headset with a hard hat to allow it to be used on construction sites.

Using Trimble Connect software, 3D models in most formats can be loaded into the mobile computer’s headset display. The models can be rotated and zoomed in on using hand gestures, to gain a detailed and accurate feel for a building’s design.

The software also has an immersive mode that allows users to walk around a structure aligned to its 3D model.

“If you were stood inside a steel frame, you could see where the columns and braces need to go,” Trimble’s technical manager Steve Jackson explains.

There’s even a chatroom function that allows other people to join at the same time so that they can all view the model remotely.

Jackson sees BIM combined with VR and AR offering advantages in the construction stage and also for facilities management once buildings are complete and operational.

Tata introduces BIM product data tool

Tata Steel has launched a BIM and product data tool for all its European construction brand products, which it hopes will allow architects, specifiers and facility managers to retrieve the exact level of BIM data they require in the format they need.

The company’s web-based DNA Profiler provides access to BIM data on over 6,100 of its products in software formats including Autodesk Revit, ARCHICAD, Tekla, Allplan and Trimble SketchUp.

Alex Small, Tata Steel BIM and digital platforms manager, says: “If BIM is to be properly adopted, the industry needs to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Our DNA Profiler provides the design community with the tools it needs and acts as a standard setter for product manufacturers.”