Rich Draper, head of BIM and digital assets at the University of Birmingham, has been at the forefront of BIM for nearly 20 years. In the first of a two-part interview, he talks about building an advanced digital twin for asset management, which has helped identify underused buildings with projected savings for the university of £400,000 – and why he’s known as the ‘BIM Viking’.

BIMplus: What’s your background, and how did you get into BIM?

Rich Draper: I have been working in the industry since 2002, starting as an apprentice in civil engineering, then architectural and landscape consultancy before moving into the university sector on the client side. I did a degree on day release in architectural technology at Birmingham City University (BCU), where I was the first student to do a dissertation design study using BIM. I graduated in 2010 – six years before the BIM mandate was introduced. Then I went back to do a bit of lecturing on the subject.

Having worked across different types of disciplines, my background gave me a good understanding of the language and context.

In 2012, I moved to the estates department at BCU to be its BIM coordinator with a brief to make the job my own. I stayed there until 2019 when I received an offer to move across town to the University of Birmingham. It is 10 times bigger in terms of buildings and student numbers, so it was the next obvious challenge for me.

“I brought in a structured approach to the information that we needed delivered, alongside absolute rigour around validation – and that’s the approach we have carried across to the University of Birmingham.”

Why are you called the ‘BIM Viking’?

I found out by accident that some consultants I was working with at BCU were discreetly referring to me as the BIM Viking while I wasn’t around. I’m six foot four with a long beard and a sort of Mohican hairstyle and, apparently, I had a rather imposing presence and being sure about what we should do and just getting on with it.

I’m told it was a term of endearment, and I thought, well I may as well lean into it, so I use it as a bit of a fun icebreaker.

You made your name at BCU – what did you achieve there?

I brought in a structured approach to the information that we needed delivered, alongside absolute rigour around validation – and that’s the approach we have carried across to the University of Birmingham. It seems an obvious thing, but in the sector in those days it wasn’t, and I’m still not convinced it is now.

As an example, when I met with the design manager of one of the main contractors we were working with at BCU and asked him if he had made sure the BIM models were correct and validated, he replied that in all his years of working as a design manager for a contractor, he had never been asked by a client to make sure the as-built drawings were accurate. So, a lot of what we did was about ensuring we were being given the correct information.

Talk us through your current role

My title is head of BIM and digital assets. It’s about ensuring the information we receive is useful and completed in the way we specified and then looking at ways to use that information to improve how we run the estate.

Something that is not necessarily fully appreciated by contractors and consultants is that clients like us do use the information beyond practical completion of a project. So, the space information starts to flow into our CAFM system and all our other systems. That could be our BMS or our timetabling system.

We’ve geared up our BIM approach to feed us with the information that we need to use going forward.

My team comprises seven people. One is performing a newly created role of building information surveyor, and they spend a lot of time in the university doing survey work, such as collecting information for laser scanning. This allows us to improve the information we have about existing buildings, which ultimately allows us to run the estate better.

We’re mostly working with information from the models every day, and that’s used across the scale, from making changes to existing buildings on a small scale to digitising our existing estate.

“Something that is not necessarily fully appreciated by contractors and consultants is that clients like us do use the information beyond practical completion of a project. So, the space information starts to flow into our CAFM system and all our other systems. That could be our BMS or our timetabling system.”

We also use the model to complete regulatory reporting. For instance, we’re obliged to report to the Higher Education Statistics Agency about our space, what it is used for and how much is vacant.

The information is also used to inform other compliance activities and maintenance. We have a maintenance backlog due to an ageing estate – and there’s never quite enough budget. Some of our oldest buildings – the Aston Webb building and clock tower, for example – date to the 1900s.

We have also delivered a successful masterplan over the past decade, and there’s a further £1bn of spending in the pipeline, including additional work to the Aston Webb building. We have 300 buildings of different sizes and ages across our estate.

What are the ambitions for digitising the estate?

When I joined, my task was to take the reins on the information side of things and get a handle on the historic information that we had and start feeding that into the operational side of asset information as well. There were lots of paper files and CAD files, so it was a big job digitising information about our older buildings to survey the estate accurately. It’s been a very valuable exercise, not least because we’ve detected numerous errors that had crept into those old drawings.

Are you looking to create a digital version of all your buildings?

Yes indeed. Currently there are two versions. We’ve got a campus version, our macro twin, which is not very detailed – each building is just like a block. Underneath this version is another with all the utilities infrastructure, which we have modelled from ground penetrating radar surveys, as well as using some historic information.

Then we will have the micro digital twins, which are the buildings modelled in detail, covering everything from boilers, chillers, pumps, through to doors and windows. That means we can ‘walk around a building’, interrogate it, and see what the floor plans are like.

We are moving all this information into the Autodesk Tandem platform, which is Autodesk’s new digital twin platform, which enables models to be compiled in a low code way. Our eventual aim is to build a model of the whole campus at this level of detail.

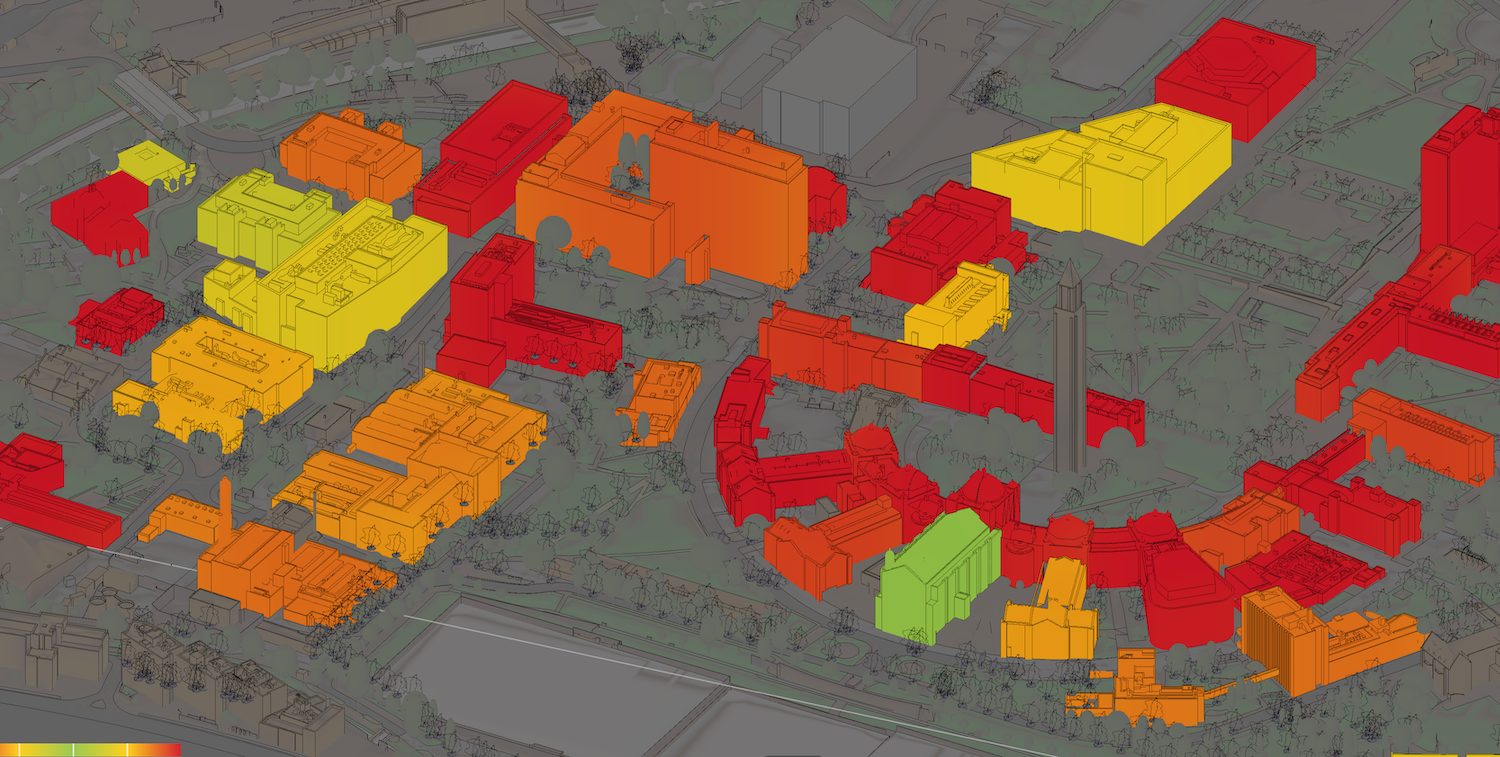

“We recently began monitoring wi-fi and heat maps in each of the buildings across the estate. The data was visualised in the digital twin and we could show which buildings were under-utilised.”

The most useful application is managing space occupancy. My team is in part the space management team and is taking a data approach to space management. We reorganised the entire space database to provide some well-structured data, which has vastly improved our reporting basis over the last couple of years.

For example, we recently began monitoring wifi and heat maps in each of the buildings across the estate. The data was visualised in the digital twin and we could show which buildings were underutilised. Based on this information, our senior management made the decision to close eight buildings, with projected savings of around £400,000 in our energy bills.

Previously, we would have sent people out to survey 300 buildings and work out which ones were quiet, but that would have cost much time and resource. By being able to show visually and in an engaging way that a particular set of buildings were consistently underused, we’ve allowed senior management to make decisions faster and more easily.

Our next project will be around net zero and space use. We want to be able to consolidate buildings not to just make monetary savings, but to cut carbon dioxide emissions. We can’t necessarily use wifi because not every room has its own wifi access point. So, we could measure CO2 emissions and temperature increases with data fed in from the sensors that the university has been investing in.

What else are you doing?

I’m carrying out a review of our operating system. We’re calling it the Project DOME review – the digital operations and maintenance environment. We see it as a collection of systems that manage the estate – the BMS, CAFM system, CDE with all the documentation and information in.

The system has been in place for a number of years, so it is time to review it to make sure we are still doing the right thing, as well as looking at how we are going to use all this information. In terms of BIM delivery, we have about 40 big projects and a series of smaller projects, all delivered against the same structure of information.

Do you follow the information structure in BS 19650?

We do and we don’t, it’s not strictly aligned. We do follow things like a strict, structured naming convention and workflows on documents and we make sure that the information provision is done in the right way. And we have our own approach to BIM information, with people in the team who police that, which is very different to what clients have been used to doing. We check the information that contractors supply us with to make sure it’s structured and correct to go into our CDE and BIM models.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.