New technology brings with it a raft of complications for contractors, as May Looi explains.

Following a visit to a 3D-printing workshop organised by Construction Manager, in late 2013 I wrote an article that questioned whether the technology was the next step in construction, and briefly considered the legal implications of this.

Just more than a year later, 3D printing appears to be the “next big thing” in construction, rivalling BIM in its capacity to grab headlines. There have been suggestions that 3D printing could help solve the UK housing crisis, and leading architects Foster & Partners and Zaha Hadid Architects have discussed its potential to build anything from a showcase pavilion to suburban homes.

Most recently, a Chinese company, WinSun Decoration Design Engineering Co, is reported to have constructed a five-storey building – the tallest using the technology – and a 1,100 sq m mansion, which was 3D printed before being assembled on site.

Beyond the headlines, 3D printing does provide great potential to fundamentally change the construction industry by altering the design, fabrication and installation processes. However, such radically new methods of working bring risks of liability and contractual issues.

This technology is evolving alongside BIM, which is intrinsically linked to progressive forms of construction, but also raises legal and contractual challenges.

Legal and contractual issues

This article focuses on the more likely immediate use of 3D printing in the UK: discrete elements or sections within a building, such as cladding panels – a goal recently mentioned by Skanska and Loughborough University.

Although 3D printing does not fundamentally change the construction process, the new technology and working processes bring potential duties and risks that should be considered at the outset to ensure clarity between parties and avoid unnecessary disputes.

First, there is the lack of established technical standards for 3D-printed components, such as a relevant British Standard. Construction team members and the client should agree a standard and, if relevant, working process, in writing, to ensure consistency and avoid a mismatch in expectations.

Furthermore, the scope of 3D printing should be laid out in the construction documents, and the position made consistent across the contracts for all the construction team. The client is likely to want knowledge – and some control – over which parts of the project are 3D printed.

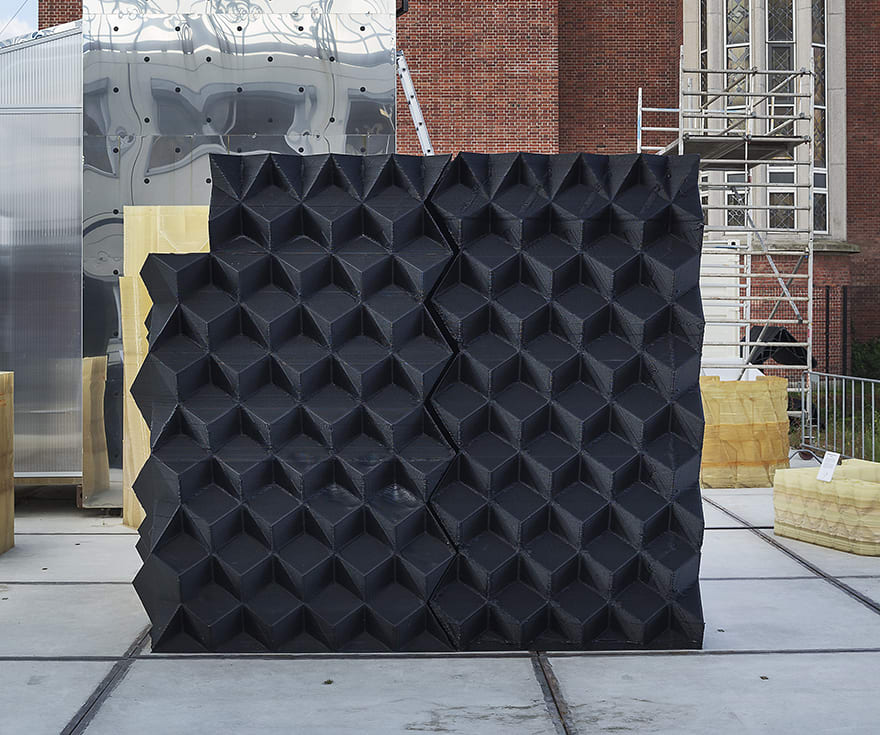

In the UK 3D printing is likely to be used for discrete elements or sections, such as cladding, as at the 3D Print Canal House project in Amsterdam. Olivier Middendorp via Hollandse Hoogte/DUS architects

There is then the issue of responsibility for any defects or imperfections in the 3D-printed objects, or damage during printing or transport. It could be said that 3D-printed elements are no different from those fabricated in the conventional way. However, to ensure clarity, it would be better to set out where risk lies between the parties, and when the responsibility for the 3D-printed sections passes from one party to another – particularly if this is different from other aspects of the project.

Given that today’s generation of machines are susceptible to dust and dirt, the parties responsible for carrying out the 3D printing will want to have appropriate warranties and indemnities in place from the machinery and materials manufacturers and suppliers.

Post-completion aspects should also be considered. The lifespan of 3D-printed building parts is still imprecise and parties will need to decide whether this affects the agreed lifetime of the building.

If maintenance and renovation of the 3D-printed elements is not expected to be as straightforward as for traditionally constructed or manufactured parts, the maintenance or handling requirements and instructions should be clearly set out to the client to avoid misunderstanding and unnecessary claims later on.

Clients may seek express terms in warranties and guarantees relating to the quality, lifespan and fitness for purpose of the 3D-printed elements of the buildings.

Finally, there is the matter of insurance. Parties should discuss with their broker whether their existing policy wordings are wide enough to cover their liability arising from the 3D-printing process, any additional warranties or guarantees required by the client and whether extensions are needed to ensure suitable cover for possible claims.

The construction industry is on the cusp of an exciting and innovative time. However, how courts will apply the established legal principles of construction law to these new technologies is uncertain. To minimise the risk of disputes, project teams will need a combination of open communication and clear contract terms that are appropriate for the particular project and the parties’ obligations within it.

May Looi is a senior associate at Kennedys

Clients may seek express terms relating to the quality, lifespan and fitness for purpose of the 3D-printed elements of the buildings.– May Looi, Kennedys