Construction has a vital role to play in the future, but its relationship with technology is problematic. Applied futurist Tom Cheesewright discusses this through the frame of the recently republished Usborne Book of the Future.

The 1970s and early 1980s was a rich period for sci-fi and those interested in the shape of things to come. The likes of Star Wars, Tom Baker’s seminal turn as Dr Who, BBC1’s weekly science and technology show, Tomorrow’s World, and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner fed young minds with dreams – and nightmares – of what the future held.

Alongside those cultural landmarks was a publishing sensation, launched in 1979: The Usborne Book of the Future. While its cover depicted battling spaceships, all lasers and explosions, each spread inside contained much more grounded visions of how we would live, work, play and travel in the next 20 to 100 years.

The book has been out of print for decades, but earlier this summer Usborne republished it, complete with a new foreword by applied futurist Tom Cheesewright.

We talked about the book’s depiction of the built environment, construction’s relationship with (future) technology, and what might come next for construction.

BIMplus: Which of the Book of the Future’s notable predictions came to pass, and which didn’t?

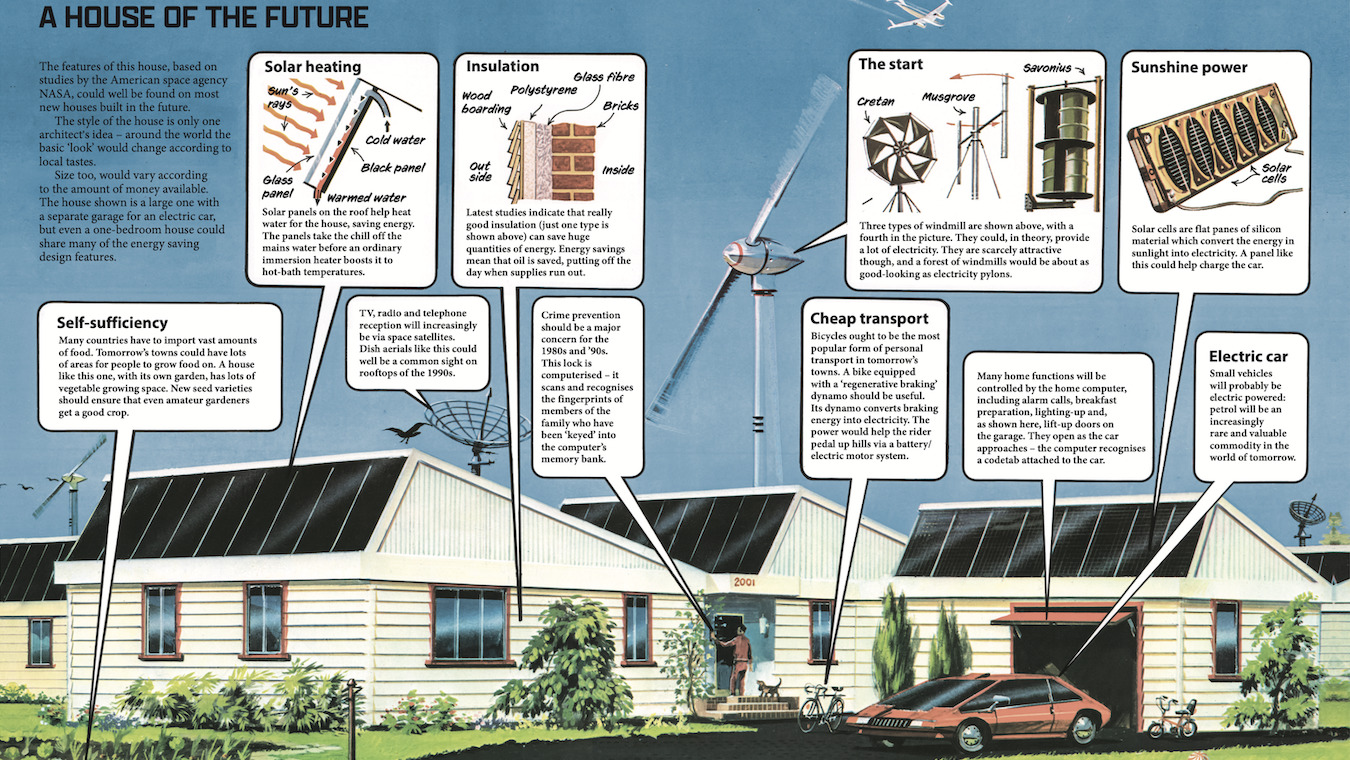

Tom Cheesewright: I think the section on future cities is a really interesting example. You look at its portrayal of both the inside and outside of the home of the future. You’ve got solar panels on the roof, you’ve got an EV outside, you’ve got wind turbines, you’ve got insulation, you’ve got all sorts of technologies that are incredibly familiar on the outside.

And the picture of the inside doesn’t look that different to reality. There’s a big screen TV, there’s a computer in the background, and there’s someone watching sports on the sofa.

There are some things that it does have wrong. Its idea of email was relatively close to fax, and still involves the use of physical copies going in and out. [The vision of the future] was still bound to the physical, to physical media, to the CD.

And its version of the internet looks rather a lot like Ceefax. But given that the authors weren’t talking about specifically what year it was, given the broad range of 2000 to 2020, it’s a pretty accurate representation.

But I think its portrayal of the potential for climate change, both positive and negative, was really prescient to show more than 40 years ago. It shows the depth of research that went into the book.

Futurologists are keen on stating that the future can be predicted, just not when it will happen. You’ve said it yourself. We’ve got robots that can print 3D buildings, robots that can lay bricks, print site plans on site, repair roads, AI that can control heavy site plant to make sure it doesn’t collide with site teams, so what’s your view of construction’s relationship with technology? And what might come next for those that work in construction?

I think it’s at times been a slightly reluctant relationship, certainly for parts of the construction industry. And yet it’s one of the industries that’s under the greatest pressure to modernise because of the challenges we have around skills, the challenges we have around profitability and sustainability, not just environmental sustainability, but actually the sustainability of many of the businesses in the construction sector, sometimes only one bad project away from going under.

“I think an architectural co-pilot, or quantitative co-pilot, or even project planning co-pilot would be incredibly powerful.”

And technology ought to be able to address some of those issues. It ought to be able to improve margins, it ought to be able to make planning more robust, it ought to be able to augment some of the less physical labour involved in the in the supply chain in the production of new buildings and the adaptation of old ones in a variety of different ways.

I look at some of the collaborative AI technologies and the potential role they have is very exciting. We’ve already seen the use of generative design in this sector for quite some time, but in quite narrow ways. I think a much broader, sort of architectural co-pilot, or quantitative co-pilot, or even project planning co-pilot to pick up on previous mistakes, learn the lessons, advise, guide, and automate interactions would be incredibly powerful.

I think there’s also an opportunity to leverage technology to solve some of the more business process problems that this sector has – that lack of joined up thinking between the different stages of construction. It still feels very disjointed so much of the time. I think there’s so much cost, so much unshared risk, and so many challenges that come out of that.

I think there’s a number of opportunities, even before we get into the really sexy possibility of robots and bionic people on the building site.

In the last few months, we’ve had alarmist headlines about AI. Given that construction is behind the technology adoption curve, do those headlines create some kind of dissonance or further disruption or delay to the industry’s adoption?

I think a lot of people in construction – and this is true of many other industries I work in as well, such as finance, professional services, technology – people will read those headlines and use them to buttress their own existing perspectives and use it to reinforce their rejection and their intolerance for some of these technologies.

That does two things: it makes the life of those who see the benefits it can bring harder; and it creates more opportunities for new entrants.

The thing that surprised me about construction, particularly in the past few years, is that we haven’t seen more new entrants who have looked at the scope of technologies available, and the fundamental shifts in efficiency that they offer, who have looked at the speed of adoption across the rest of the industry, looked at the competitive landscape and said ‘we could hoover up a load of venture capital’ and ‘we could build a very different form of construction firm’.

The slower the industry and the existing players are to adopt these technologies, the more likely it is someone comes in with a big wad of venture capital behind them and chooses to do things very differently. And even if they don’t succeed, it will fundamentally disrupt the market.

What’s your favourite illustration in the Book of the Future? Aside from the space battle on the cover of course!

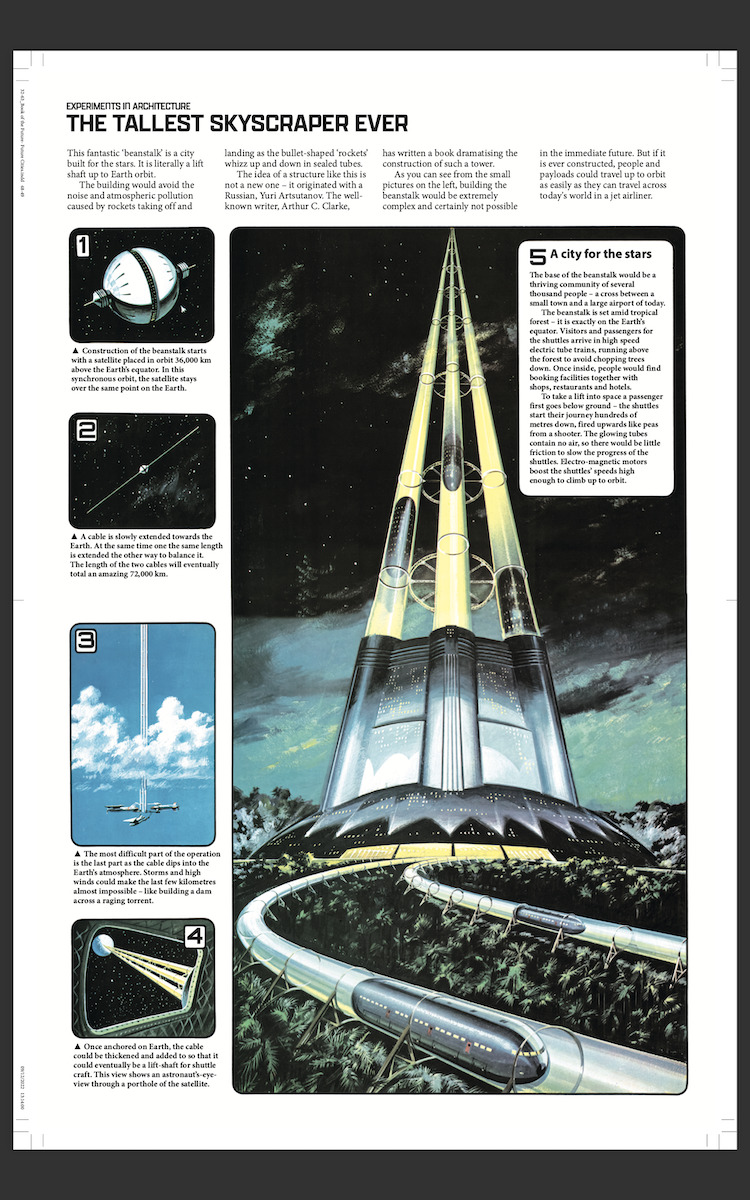

That’s a really good question. The one I find myself talking about a lot, and it’s one of the most unlikely and impractical illustrations in the book, is the space elevator. I love this idea that we could have a permanent and less carbon-intensive connection to the rest of the solar system and ultimately the rest of the galaxy.

I am a big believer that we ought to spread out into the solar system. Ideally we learn from some of the mistakes we’ve made on earth before we take those mistakes with us.

But it’s there to be explored. So the idea of a space elevator, which would look nothing like the one in the book, absolutely appeals. If you’re going to do another moonshot for humanity, a shared global goal, to better connect us with the solar system, I think that will be a very good international project to focus on.

You can listen to some of this interview in July’s episode of the 21CC podcast.

The Usborne Book of the Future is available from all good book retailers.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.