- Client: Hill Group

- Lead Contractor: Hill Bespoke

- BIM Tools: Autodesk Revit, BIM 360 Field

Point cloud scans, BIM, iPads, digital setting out… this is the story of how an unlikely small-scale project in Cambridge became an exemplar for building using today’s high-tech tools. Denise Chevin reports.

This article was first published on BIM+’s sister site Construction Manager.

A rural housing development on the outskirts of Cambridge is the unlikely setting for an exemplar in digital construction. But the Hill project in Trumpington, Cambridge, really does have it all. Point cloud laser technology is used to create a scan of existing buildings on the site and the BIM model produced from it is used to take off bills of quantities without the need for an external quantity surveyor. Setting out is also done digitally, so reducing the cost of site engineers.

What makes this scheme even more remarkable is that it is a relatively small project and involves the restoration of complex and dilapidated Grade II-listed barns.

Add in the use of cross-laminated timber panels manufactured in factories and craned into place on site and what you have is a microcosm of cutting-edge construction within the confines of a 12-home development.

This is not so much a trailblazer for BIM as an example of how a fully digitised approach is viable, achievable and beneficial to reduce waste and cut costs, even on small conservation projects, says David Miller of David Miller Architects (DMA). “The clients’ approach has been to look at digital technology to unlock the viability of the site,” he says.

The digital approach potentially saved tens of thousands of pounds by allowing the team to get things right and reduce the risks that often dog complicated historic conversions.

DMA has worked on a number of collaborative BIM projects, which was one of the reasons the practice was selected.

“We wanted to demonstrate that complex technology can apply to pretty much any project,” says Miller. This was very much the ambition of the client too.

When complete the project will deliver 12 homes from seven converted barns and four new builds

The scheme is an example of how a fully digitised approach is viable, achievable and beneficial on a small conservation project

The driving force behind harnessing the new technology was Mike Beckett MCIOB, managing director of Hill Bespoke, a subsidiary of Hill Group, the ultimate client for the £7.6m project.

The project comprises the conservation and refurbishment of a group of historic barns and other agricultural buildings dating to the 18th century. When it’s complete in March 2017, Hill will have converted seven barns into eight homes and built another four houses in two blocks from scratch. The development is in the grounds of a former stately home, now a hotel, and is aimed at the high-end market with prices starting at £1.25m.

Some of the barns have complex timber structures and are Grade II listed, while the remainder have single-skin masonry walls. To turn them into modern homes the team reached for different construction techniques, including slotting steel frames into the carcass of the timber barns to support the new upper floors and the roof. They were also enlarged with glass, or extended with masonry construction with timber cladding and zinc roofs (like the new-build units).

The semi-detached new-build houses have masonry construction with structural insulated panels on the roofs, which are then clad in zinc. Their facade is stack-bonded brickwork and green oak rainscreen cladding, which draws on the local vernacular. Throughout the process a great deal of masonry was recycled from the existing buildings and redeployed.

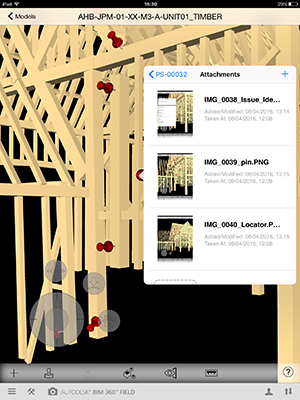

Onsite staff were equipped with iPads so they could refer to the 3D model on site

Miller says of the barns: “They are irregular and dilapidated and fairly rare in Cambridge and therefore of particular interest to the conservation officer and English Heritage. We had to develop robust techniques so conservation officers were happy with what we were doing. This included kitting out specialist conservation carpenters with iPads so they could work to the 3D model and make a photographic record of the work that has been carried out.”

The technological approach helped make the project viable. Beckett has written a BIM strategy for the entire group, but it’s the first time they have taken the digital approach for a conservation project.

“It’s a challenging project and we decided just to grab hold of it. If we can engage with BIM technology for historic fabrics we can it do for anything,” he says. “Our vision is to be the leading, most trusted provider of distinctive, quality homes and the BIM strategy is line with that vision.”

Beckett says that one of the key drivers for harnessing BIM across the group is that Hill does a great deal of work with registered social landlords and wanted to ensure that in future partners would not miss out on funding because they were working in a joint venture where they were not meeting any mandate requiring Level 2 BIM. Unlike other government agencies the HCA does not yet stipulate this, but Beckett is convinced it won’t be long in coming. “People who want to stick with spades, picks and shovels will no longer be in business,” he says.

For this scheme Beckett says one of the main goals was to capture the condition of the existing buildings accurately, so the team could marry up this information with the new design, prevent clashes and increase productivity. An estimated £25,000 was saved due to the prevention of steel clashes.

In terms of lessons learned, Beckett says that next time they would spend more time on clash detection and review in a more formal way. And also lower their expectations a little: “Just because you can model it, doesn’t mean it’s right.

The 3D model needs to be rigorously reviewed and the time needed to do that should be understood.”

Offsite CLT improves buildability

Another innovative aspect of the project was the use of offsite-manufactured cross-laminated timber panels. The main reasons for using the CLT panels were to improve buildability — as the internal walls reach up to 9m high in some locations — and provide a more open-plan layout. The steel frame that was initially proposed was deemed to add too many constraints to the design.

The structural support for the walls and roof was formed by a new steel table, which sits on the ground floor. The panels were manufactured in Austria and delivered to site and craned into place. This meant no temporary works were required and the job was completed in 10 days.

Using the information from point cloud laser scans, the architects were able to provide the CLT manufacturer with details of the precise heights and outline of the gable end walls, allowing the panels to be cut to precise dimensions.

What technology was employed for the project?

Even before the architect was brought in in August 2015, Hill’s Mike Beckett had decided that it would be a digital project and rather than surveying the barns in the traditional way he employed point cloud laser scanning to capture an accurate picture of the existing barn structures.

With this technology 3D scanners measure a large number of points on an object’s surface, and often output a point cloud as a data file. The point cloud represents the set of points the device has measured. The technology is becoming more commonplace and costs have fallen. Beckett says that some of the technology suppliers were keen to be involved on more of “trial basis” with the hope of getting more work in the future, which also brought the costs down.

Architect David Miller Architects then used Autodesk Revit to create a section through the point cloud and build a 3D model, which the new designs were layered on to. “We worked closely with structural and M&E engineers in common data formats to share the model,” says Beckett. “Software packages included (Autodesk) BIM 360 Field, Glue and Docs to share information for both design and construction. Glue, for example, allows the client to view in 3D, mark in comments and send back, rather than sending Requests for Information.”

Point cloud scans were carried out and DMA used Autodesk Revit to build a 3D model from them

“The client was much more willing to take the common data environment further than most,” says project architect Katie van der Schaar-Wood from David Miller Architects. “For example, the carpenters had iPads and had access to the 3D model. They used them to verify the works to the existing listed structure of Barn 1 by photographing the condition before, during and after the work directly into the model. This technique is being developed for snagging, but used here in an unusual way.

“It provides a clear audit trail for the client and also satisfied the planners. The team has estimated that it could have saved as much as £20,000 by shaving off three weeks of time that it would have taken to write up the report in the traditional way,” she adds.

The BIM model was created in a way that meant bills of quantities could be taken off directly, eliminating the double handling of information, saving £25,000 in fees and halving procurement time.

“Normally a project like this involves a huge amount of risk and contingency, with historic building you’re discovering new things all the time,” says van der Schaar-Wood. “It’s a refreshing approach by a client keen to try out new ideas. And forced everyone to be really collaborative in a no blame environment.”

The biggest challenge? “Quantity take-off. Before we started the project we had a more theoretical view of quantity take-off (QTO),” says David Miller. “As a team we have developed a detailed knowledge of the process, which has involved adapting our modelling techniques and how to organise and present information. We have also enhanced our internal procedures for reviewing information in 3D. These are being rolled out to benefit all our projects, particularly the new ones where we are working with Hill Bespoke.”

360 Field was used

For Hill’s Beckett, being able to generate quantities from the model was a huge advantage because it shaved three months off the procurement process. He says that providing subcontractors with more information rather than the usual taking off drawings garnered more tenders, which were returned more quickly.

A final plank of the digital strategy on the project was using (Autodesk) Point Layout to set out the position of the new buildings, roads, drainage and new elements within the existing buildings. “This process has speeded up the project and improved accuracy. Furthermore, the technology also supported the verification of existing construction after partial demolition so that the CLT structure fitted within the confines of historical masonry,” says Beckett.

He adds: “To ensure the models were an accurate representation of the existing condition (and due to discrepancies we discovered between the topographical survey and point cloud scan) we also used it to validate the size and location of the existing barns. This was key for the digital QTO process. The design team have since been able to provide setting out information to the site team based on live, federated models.”

Using this model-based setting out has saved time for both design and site teams. “Our structural engineer, Gemma Design, has estimated a 75% time saving through not having to produce setting out drawings,” says Beckett. “The site team have found that its saves on downtime as trades are not waiting for a setting out engineer. Overall it is also more accurate as we are using a federated model to set out using a shared coordinate system. So much so that on future projects Hill will lessen their allowances for risk and contingency.”

The client was much more willing to take the common data environment further than most. For example, the carpenters used iPads to verify the works to the existing listed structure of Barn 1 by photographing the condition before, during and after the work directly into the model.– Katie van der Schaar-Wood, David Miller Architects