How do you use technology to humanise the built environment? Pablo Zamorano reveals how Heatherwick Studio is addressing this challenge.

As the designer of hugely popular Coal Drops Yard in London’s Kings Cross, the iconic structure, Vessel in New York, and the Cauldron for the Olympic Flame at London 2012, Thomas Heatherwick has a reputation as one of most imaginative designers on the planet. Now, not content with banishing boring buildings with his own work, Heatherwick is on a 10-year global mission to confront the public health issues caused by boring buildings and inspire the public to demand better or, to use his campaigning term, to ‘humanise’ our new structures.

His practice says studies have shown that being surrounded by boring buildings that lack visual complexity increases cortisol levels, causing higher levels of stress. Heatherwick’s Humanise campaign suggests one simple rule: that a building should be able to hold your attention for the time it takes to pass by it.

So, with this mission to bring more joy and evoke human feeling into the built environment, where does digital technology fit in?

“We try to visualise everything nowadays quickly through Enscape. If we want to make animations or immersive experiences, we’ll use the game engine, Unreal.”

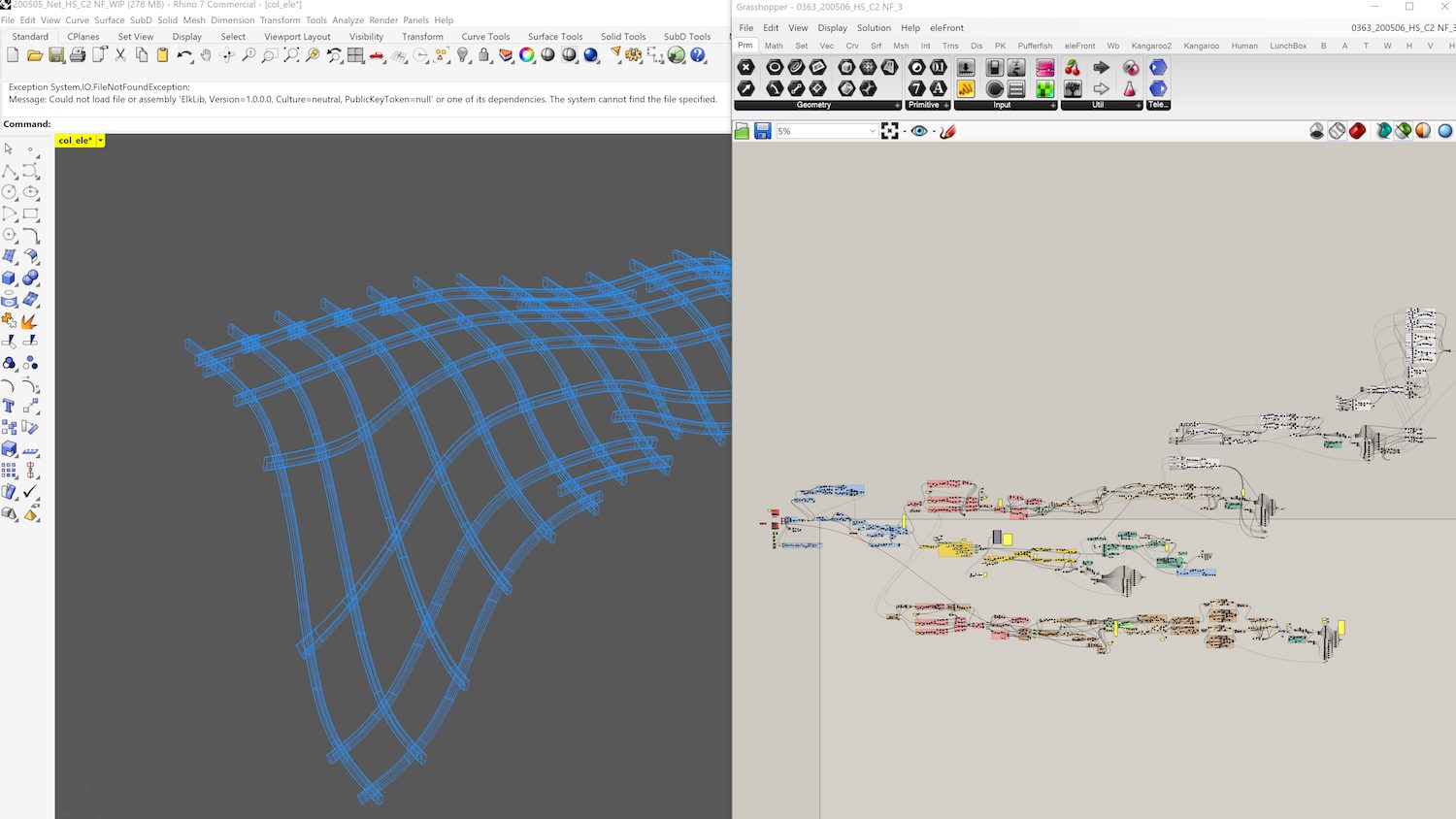

Enter Pablo Zamorano, senior associate and head of geometry and computational design at Heatherwick Studio. He has been advancing the sculptural forms of Heatherwick’s designs through the integration of AI and machine learning, and the use of tools like Rhino and Revit, and custom plugins for BIM and visualisation.

His team – known as Ge-Code – includes specialists in environmental design, AI, XR and geometry, and works across the studio’s current 25 projects globally. The studio has grown to 250 staff.

“In terms of design, we try to focus on simple ideas that will have a positive impact, but the fact that an idea is simple doesn’t mean that it’s not going to have high levels of complexity and an extra level of design, which is aided in the background by sophisticated tools,” he says. For example, on the design of Azabudai Hills in Tokyo, extensive computational design was used to parametrically control the geometry during the design, as well as to rationalise it and to incorporate material and fabrication constraints into the model.

So how does his team harness technology and where is it all going?

BIMplus: Talk us through your career

Pablo Zamorano: I have been at Heatherwick for about nine years and in that time my role has evolved. I’m an architect and I was deputy project leader for Coal Drops Yard. I still work on projects, but when the studio grew in size, it was recognised that to do so and work globally across different markets we needed to build up different kinds of support teams: a group dedicated to computational design was one of these teams. Fortunately, designers in the studio already had a high level of relevant skills, so it was quite evident that we needed to keep nurturing that and to keep on developing outside the studio in a way that could potentially help our projects.

I took the lead on this and recruited the team. It embraces a multitude of specialisms related to computational design including advanced geometry, parametric and environmental analysis, XR (AR and VR and gaming technology) and machine learning and AI.

I studied architecture in Chile and graduated in 2004. I’ve practised as an architect ever since, but I’ve always had a passion for technology as well. When I moved to the UK in 2010, I did a master’s in emerging technologies in design at the Architectural Association, and that opened my eyes to a much wider spectrum of computational tools and innovation.

How does the studio harness technology to deliver on designs day-to-day?

It’s about optioneering [creating different design options that are visibly related to specified parameters; it can be used to explore a space quickly], fast 3D modelling of very complex ideas, but also parameterisation, rationalisation, analysis, prototyping, fabrication and then the incorporation of extended reality. We do all this daily, and then in parallel, we carry out research and development on how to make our design processes better in engaging with new fabrication technologies such as robotics and developing digital products. Ideas are still conceived by sketches. We apply technology to make ideas reality, not to come up with the ideas.

We share our knowledge through activities like training sessions and workshops and we host hackathons where engineers, for example, join in as well.

And we have people who specialise in AI or XR or geometry and app development.

I don’t think there is any project we work on where a computational designer is not needed.

Iterating designs for a 50,000 sq m modular, yet not repetitive, complex facade for a museum design in Jeddah would not have been possible without computational design.

Do you use off-the-shelf software or develop your own?

We use both. Our main software for design is Rhino. Every designer working in the studio knows how to use Rhino and can create complex 3D models with it. We also have people who can interact with Grasshopper to use parametrics for some of their design tasks.

We have a smaller group of people who can use Revit, which we deploy for BIM deliverables and the production of drawings – we have a dedicated BIM team that helps us achieve that. And we work with other kinds of off-the-shelf tools for visualisation. We try to visualise everything nowadays quickly through Enscape, which is a real-time rendering and VR plugin for Rhino. If we want to take things further and make animations or immersive experiences, we’ll use the game engine, Unreal.

We have software that allows us to communicate smoothly between Revit and Rhino, and we have our own custom tool called Metrics. This is a BIM plugin for Rhino, which lets us add information to the Rhino geometry without using Grasshopper, so every designer in the studio can use it without the need to know scripting, Grasshopper or Revit. It also allows us to add levels to buildings, like geometry, or automatically produce schedules and generate drawings.

Where do you see major developments coming from?

“We are an AI-optimistic studio, we are not afraid of it, probably because we have never been afraid of technology, or any kind of tool.”

I believe that AI will profoundly change the way we do things across design and construction and engineering. We are an AI-optimistic studio, we are not afraid of it, probably because we have never been afraid of technology, or any kind of tool.

We began researching custom image generation workflows many years ago and also tested off-the-shelf image generation models for visualisation as an easy way to understand the technology. But it quickly became apparent that there were privacy issues around who would own these images. So that led us to start developing powerful generative AI tools in the studio. We have developed software that runs our custom models for image generation and we’re also working on a large language model that searches our internal documents.

As well as privacy issues, there is also the possibility that when using off-the-shelf software, it can generate poor, generic results. Image/information is generated from prompts on the same models, so everyone who asks a similar question will come up with similar results.

Is AI already changing how you do things?

Yes, instead of doing a render, I will write a prompt or use one of our styles, or simply pick one of our images as a reference, and then get an AI image from our tool – that’s one thing that’s already changed. I think the real question now is whether we will continue doing what we do. We are still architects, and the outcome of using AI is still going to be buildings or things that are kind of physical, but the type of roles within firms are changing. The fact that we and others already have people who are experts in AI is testament to that.

There’s much curation and checking that needs to be done when you are working with generative tools. The production time may be through a robot, and then you will have to focus much more on critical thinking.

I think that’s a good thing. But it’s also about paying attention to your values. So in our case, that’s all about the human impact of the things we design. Understanding where your values lie is one of the key elements of these new processes.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.