Bryden Wood, the integrated architectural and engineering practice, brought the concept of a platform approach to design, which was adopted by government for its prisons programme. Since then it has evolved the idea of templated designs to offer standardisation and flexibility to suit varied sites. Jaimie Johnston MBE, a board director at the practice and brains behind the platform approach, brings BIMplus up to date.

When it comes to turning design and construction from a site-based process into something finely honed, digitally-based and factory-fabricated, Bryden Wood has been at the forefront. Central to its thinking has been so-called platform design – a digitally designed kit of parts manufactured in a factory that can be used across many kinds of asset.

In doing so, it creates a high-volume, consistent demand so that a wide, diverse supply chain can make use of the common components, akin if you like, to the approach Ikea takes with its components for flatpack furniture. This, of itself, creates economies of scale and dramatically increases productivity.

The concept of a platform-based approach has gained traction within government. In 2021 the Infrastructure & Project Authority set out a plan for mandating platform design for manufacture and assembly (PDfMA) in the Transforming Infrastructure Performance: Roadmap to 2030.

“Often clients procure a bespoke design for every site, introducing unnecessary design cycles and complexity that adds cost and time to construction projects and ongoing operations.”

Demand for flexibility

The idea of platform design is that a kit of parts can be configured to suit a specific design and site. But some clients with larger ambitions want to adopt design templates not just for components that are designed for manufacture, but all the components of the building. As Jaimie Johnston explains: “Many major clients have national or global rollouts that are happening at a rapid pace. Often these clients must procure a bespoke design for every site, introducing unnecessary design cycles and complexity that adds cost and time to construction projects and ongoing operations.

“Yet, from our experience, these clients have a very well-informed view on how their asset needs to perform and the layouts and designs that deliver their operational outcomes. This knowledge and understanding lends itself to a repeatable solution that can comprise around 80% of the asset.

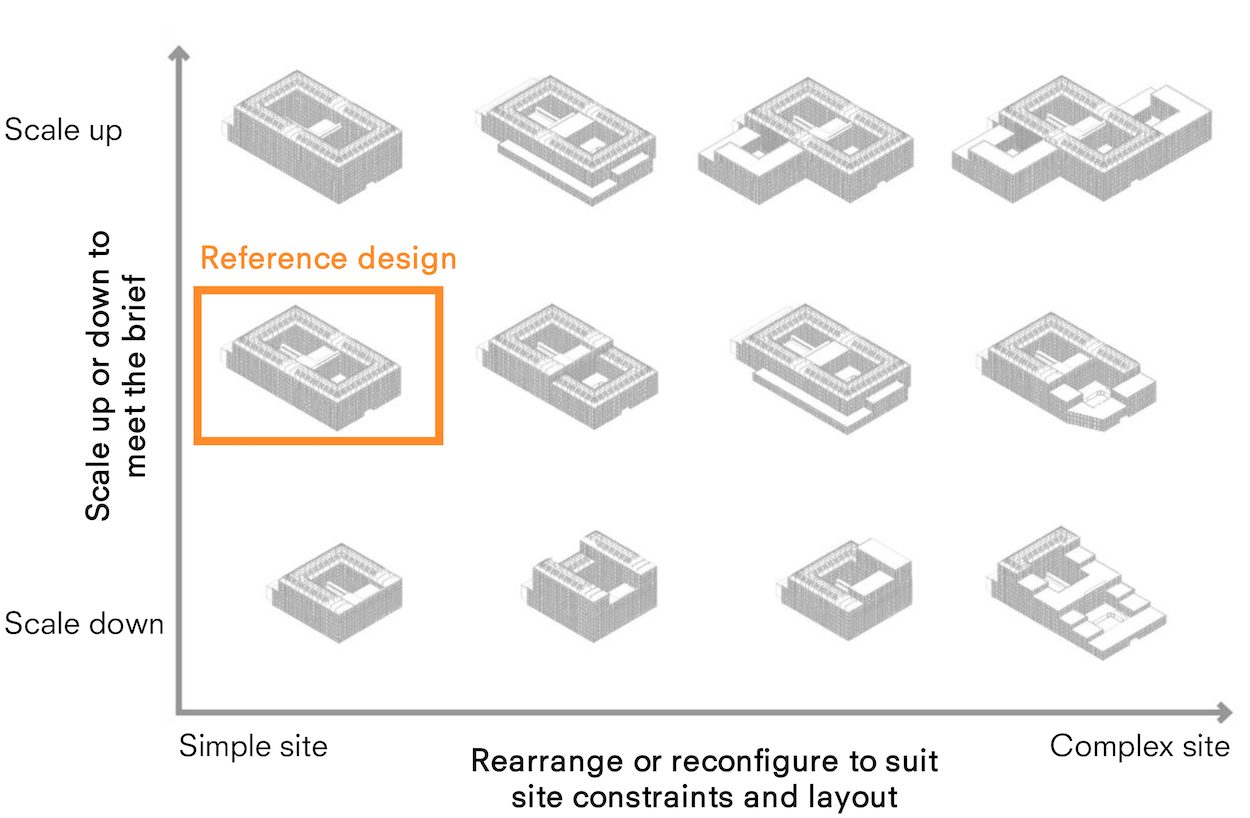

“We call this a ‘reference design’: a highly optimised, site-agnostic core design for a portfolio client.”

Introducing reference design

Johnston explains that a reference design contains several repeated elements that can be configured in many ways. These repeated elements could be anything from key equipment to whole blocks.

For some projects, the reference design can become the fixed design for all the client’s projects. “The house blocks we designed for the Ministry of Justice prisons rollout are a good example. Highly standardised, they are identical on every site. Only the number and orientation changes and that’s dictated by the prison population and aspect/prospect of the site. The UK prisons rollout is reporting dramatic reductions in delivery schedule with much-improved certainty on just the second project to use this approach.”

Johnston explains that, critically, reference designs as envisioned by Bryden Wood have more flexibility built into them than conventional templated designs. This is important because where projects need to respond to site constraints and/or business needs, if there is no flexibility, then the templated design can end up being unravelled and the client is effectively paying for new designs.

“Most clients need designs that can respond to unique sites and needs,” says Johnston. “So, for example, for a healthcare facility the design needs to be flexible to accommodate specific clinical specialisms and the demographics of a particular region.”

Chip thinking

So how can a reference design both standardise a design, yet leave enough flexibility to adapt it to any given brief? And what is the relationship with platform designs?

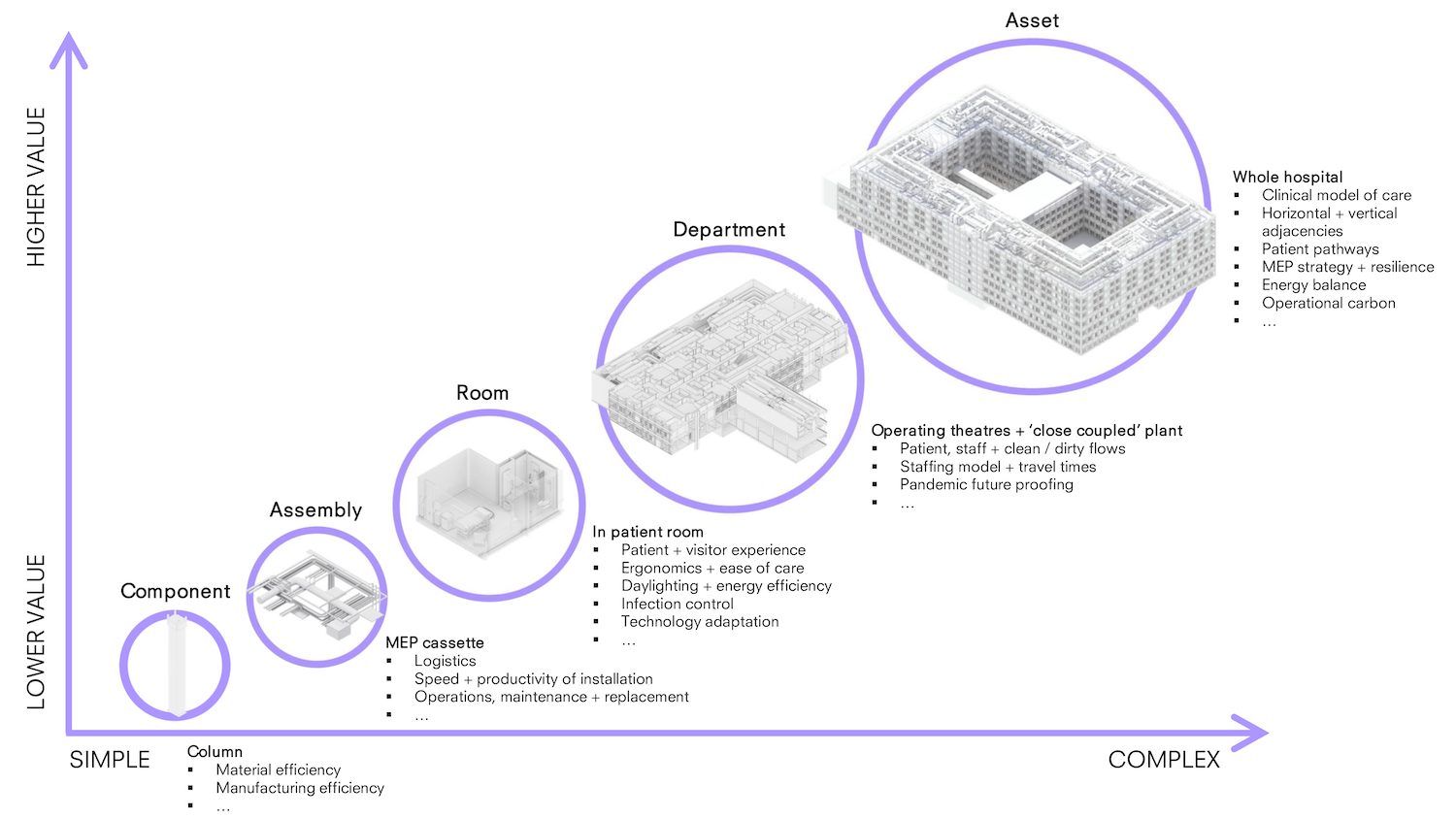

That’s where what Bryden Wood has dubbed ‘chip thinking’ (and trademarked it) comes in. This breaks down the design of an asset into packages of components and processes, which it calls ‘chips’.

“Chips are sets of interacting or interdependent components, plus all the data that goes into them. It’s like computer chips – you’ve got a computer chip that has certain capabilities, you plug a series of them together to make a computer.”

“We’re seeing that this approach is super applicable across all sorts of sectors. I think chip thinking was an idea slightly ahead of its time. But it all makes sense.”

Chips are created at all levels, from pieces of equipment to a whole room. The reference design can be largely created by combining these chips in the most efficient way. Johnston says the reference design can then be built again and again as a fixed product by clients who have control over site conditions, as the MoJ had for its house blocks projects. The first of these new-generation prisons opened in 2022 in Wellingborough and houses 1,700 prisoners.

But for those who need flexibility, the reference design becomes far easier to configure flexibly into a physical asset when broken down into its chips. Says Johnston: “By digitally modelling the design against the given brief/constraints using chips, we can quickly see how well the design will work, and what we can adapt to fit the wide range of needs and constraints involved. This ability to adapt the configuration of a design would be impossible in a design expressed as 100% single components.”

The ‘local’ design is then focused on ground conditions, utilities, infrastructure, placemaking, and flows of people, for example.

Chips in hospitals

Johnston says that Bryden Wood introduced this concept to the NHS hospital programme (announced in 2020) to build 40 hospitals, developing the initial ‘Hospital 2.0’ solution. While Hospital 2.0 has since evolved, the use of a reference design continues to be a central part of the strategy to deliver schemes across the UK.

“We are currently deploying reference design and chip thinking across the private sector, particularly in the data centre market and for logistics and fulfilment centres,” says Johnston.

Reference design in a traditional supply chain

The concept of reference design and chips works well with PDfMA, but it also works with traditional construction methods if supply chains are not mature enough for PDfMA. One of the benefits is that in taking this approach allows designers to focus more of their efforts on solving the site and context-specific challenges.

Critically, reference design gives teams the ability to assess a site very quickly using a ‘test fit’ process. For example, Bryden Wood has developed an app that can configure potential options for a school site in 10 minutes, an apartment block in half an hour, and a motorway in an hour.

“At this speed, we can beta test many more options than could usually be considered. So, to give you an example, the houseblocks we designed at Five Wells prison in Wellingborough did not even have a traditional brief. Instead, the client said the outcome we want is to tackle recidivism. Reoffending costs billions of pounds every year for the taxpayer, ‘How would you design a house block in such a way that it helped tackle that?’” The cells have no bars on the windows and prisoners have access to a gym and snooker tables.

Deep analysis

Johnston explains that Bryden Wood carries out deep analysis of the needs of the client before drawing up designs, including using data analytics.

For example, when it was working for healthcare provider Circle, data analytics had shown that the hospital needed one fewer operating theatre than the client had originally anticipated.

Johnston says that although the practice has been thinking along these kinds of lines for some while, it has only recently begun to articulate the link between chips and reference design. It is something his Bryden Wood colleague, senior associate Giuseppe Miccoli, spoke about at Digital Construction Week.

“We’re seeing that this approach is super applicable across all sorts of sectors. I think chip thinking was an idea slightly ahead of its time. But it all makes sense because of so many clients have large construction programmes where the design needs only differ in terms of site constraints, and flexible templated design makes sense.”

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.