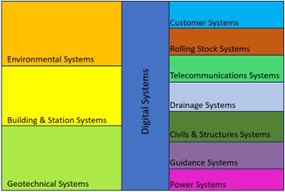

Traditional approaches to infrastructure development often focus on individual components or subsystems, overlooking the intricate interdependencies and interactions among various elements. However, Iain Miskimmin believes the adoption of a ‘systems of systems’ is a powerful strategy to overcome these challenges.

It is also clear that the systems of systems approach needs to be grounded in the digital space, so that, as a foundation layer to building digital models, shadows and twins, we can optimise the planning, designing, constructing, operating, maintaining and ultimately decommissioning our built environment.

To optimise the systems that are proposed, from the start, we must better understand their function, how we can measure/monitor their performance, and how they interdepend and interface with each other.

While what colour something is painted, what material it is made from and who designed it are all important pieces of information, only through the measurement of function and performance and its optimisation will we really start to see significant benefits from our digital endeavours.

Outcomes not specifics

When defining a set of Function Information Requirements (FIR), it is important to understand that we want the best outcome, not a closed thought loop.

Nobody has the best ideas for everything, we are all encouraged to collaborate. But this is not just sharing a few files, it is about sharing ideas and working out the most effective way this information can be measured, monitored, managed and communicated.

This, hopefully, allows the appointed party to demonstrate how innovative, collaborative and all-around good they are.

Early optimisation

During the planning phase of a project, the appointed party will set out the basic building blocks that will eventually lead them into the more detailed phases. But understanding what each of their systems are, defining their function and whether their performance will deliver the client’s outcomes is an essential start.

Defining basic function and performance criteria for each high-level system, then asking the appointed party to suggest the best ways they can measure and monitor this (plus any additional information that might make early critical decisions easier), will pay dividends as we move through subsequent lifecycle phases.

The interfaces between these high-level systems, their capacity and the resilience levels of both the systems and their connections will become increasingly important as the project progresses, allowing critical decisions to be made on future operational efficiency, criticality, vulnerability and potential expansion options.

Expanding what is known

In the early phases of a project, only a limited amount is known about the details of the systems or the physical assets that will perform their functions, let alone the detailed information that will be vital for their construction, operations or maintenance. This can be built on, as the project progresses, as we understand the equipment and technology that will be used to achieve the client’s desired outcomes.

Function (System) Information Requirements

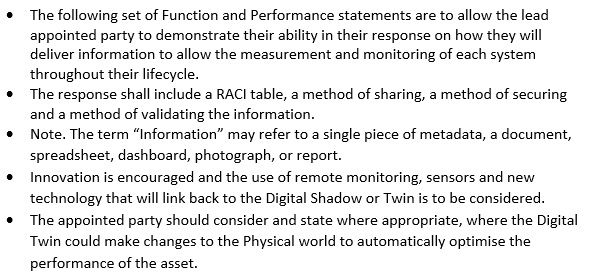

The information requirements are based around a series of function and performance statements that will allow the lead appointed party to generate, manage, share and provide assurance using their best methods, procedures and technologies.

Remember, information collection, verification and storage costs time, money and carbon. So the client needs to evaluate what is valuable to them, as not everything will be important enough to procure.

This approach gives the appointed party the freedom to use the latest innovations, technologies and thinking to deliver the outcomes the client desires.

The client’s statement before a table of functions and performance requirements in the FIR could read something like this:

Function and performance example

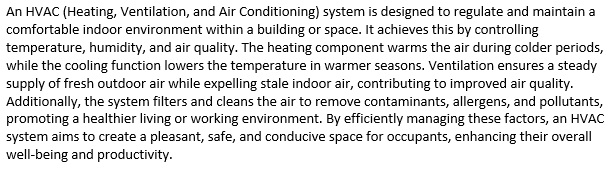

It would be easy to assume that everyone knows the function of something. However, this can be a dangerous practice, so stating the function of the system is important to ensure we are all talking about the same thing. For example:

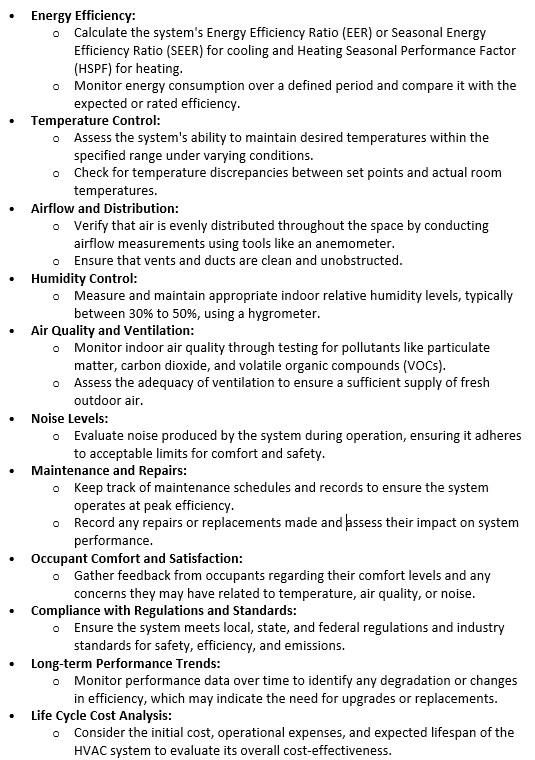

Now all the parties have agreed how to describe the function, the client can also list what performance criteria they feel is valuable to them and the optimisation of the asset throughout its lifecycle. For example:

The appointed party’s response should not be taken as a definitive, but as a basis to discuss and improve, the way a true technical partner should in a project.

Systems inside systems

As the project progresses through its own lifecycle, each of the high-level systems will become more detailed, revealing their own subsystems. At each phase, the FIR needs to be revisited and refined until finally reaching the construction phase, where the contractor will specify the physical thing that will carry out the function and deliver the specified performance.

This steady build-up ensures that the focus is on what is valuable for the next phase and doesn’t overload the information management team at the beginning, where traditionally little investment is made in the digital model, shadow or twin.

Minimum generic information

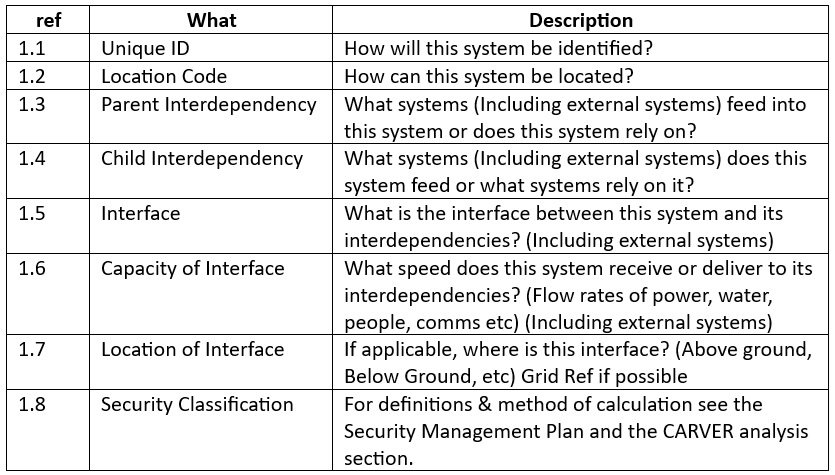

As with all information requirements, there will be a generic set that applies to all. This usually contains some sort of location coding and means of identification. But with systems and, more specifically, systems of systems, we need to understand the connections and interdependencies.

Those connections and their interfaces will have a type, location and capacity that needs to be understood to help the designer, constructor, operator and maintainer to know how critical and vulnerable they are. They will also indicate how much more can be generated from the system in the future.

Looking at the bigger picture, outside of the project, and how this new asset will interdepend with other existing systems, across multiple sectors and owners, allows a possible easier interaction with the National Digital Twin programme.

Finally, this information can be pushed into a CARVER analysis to define the security classification of the system in question, plus the information that goes with it. For example:

In summary

Information requirements to the level of detail required to put together a true digital twin can be a daunting and expensive task, especially if tackled before a project is launched and the nature of the assets (both physical and digital) needed to deliver the client’s outcomes are truly understood. So aiming at high-value information, looking at function and performance of the systems and then their subsystems, can set a good foundation for the entire lifecycle without costing a fortune in time, money or carbon.

Defining the outcomes rather than the specifics allows an innovative and forward-leaning appointed party to really show how good they are and the value they can bring to the project.

There are multiple bonuses that can be achieved with this methodology from interfacing with the National Digital Twin through asset optimisation, to defining security classifications.

A low-hanging fruit with a high value: why wouldn’t you?

Iain Miskimmin is digital adviser at Nec Aspera Terrent Digital Ltd and Bentley Systems

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.