When BIMplus last interviewed Martha Tsigkari and Adam Davis in Foster + Partners’ Applied Research + Development (ARD) group, it was a time when Spot the robot dog, AI and using gaming engine software were at the forefront of their work. Three years on, what they are turning their attention to now?

The ARD group at Foster + Partners continues to pioneer cutting-edge technologies, often drawn from other sectors, to improve the design experience for the firm’s architects. Now 24-strong, more than double its 2021 number, the team is embracing AI to visualise different design options, has developed its own AI-driven search application using large language models (LLMs), and is even looking to explore commercialising some of its in-house developments.

Tsigkari, senior partner and head of the ARD group at Foster + Partners, and Davis, a partner at the architectural practice and deputy head of ARD, explain that, to date, developments have been for the use of the group, who would then aid architects in their work. Now the emphasis is on developing software and products that the architects themselves can use across their practice.

BIMplus: How are you applying machine learning?

Martha Tsigkari: We have been looking into machine learning in different areas. One of these is LLM – most people are familiar with the term from ChatGPT. Through them, we’re developing applications that can help us disseminate knowledge and information throughout the office. So we have our own Ask F+P application, internal to the office. Through that, Foster’s staff can interrogate all our design guides using natural language queries and get direct answers from these guides.

“If you do ideation through the applications that are available online, you lose IP and copyright. And it’s not the best thing for your data.”

How does Ask F+P work?

MT: Our design guides have been developed over decades. They give us guidelines on design specifications and how we design things effectively.

These are written as multiple PDF documents. So if you have a question, rather than just trying to scroll through the guides to find what the answer might be, you can ask a question in natural language. For example, what is the best insulation that I can use for a commercial building?

The software uses semantic search, which means it can understand the underlying meaning of the query and identify related concepts and synonyms, in contrast to searching for keywords, which relies on matching specific keywords or phrases in documents or databases.

The application will go through the guides and will provide – within a level of confidence – the best answers from them. It will also point to the location in the PDF where you can read and see how close this matches the query you made.

It is in beta right now and being used throughout the office. And we’re looking into expanding into different data, so we can search other datasets beyond design guides.

Are you using AI for design purposes?

MT: We have used a locally hosted copy of Stable Diffusion – an image-generating AI software based on diffusion models – to create a plug-in for our design software. It allows designers to ask the computer to make suggestions on top of the model they have created. So we’re not asking the machine to imagine things for us. Rather, the machine may help us with the visualisation of the things we’ve already designed, like adding photorealistic lighting effects or texture of materials.

We’re also looking at developing our own machine learning portal that could form the basis of a portal for investigating image-making through our own models.

Why are you looking to develop your own software?

MT: Providing more bespoke solutions to clients allows us to customise and future-proof our workflows and deliver real-time performance-driven solutions.

Particularly in relation to machine learning, MidJourney is an AI application where you can request the system to imagine things for you. So you can write, “I want you to show me a dog that walks in space” and it will give you an image like that.

There are a lot of architects using these sorts of applications just to generate images. But architecture is so much more than image generation, although we see the value of being able to quickly do ideation through things like that.

However, if you do ideation through the applications that are available online, you lose IP and copyright. And it’s not the best thing for your data. So we are creating systems to do ideation in-house with systems hosted on our own servers.

Is the development of AI having an impact?

MT: It will have a bigger impact as we go forward. We are trying to see how these technologies can facilitate and create better design, but without stifling or eliminating our creativity and instead augmenting our creativity.

What about digital twins?

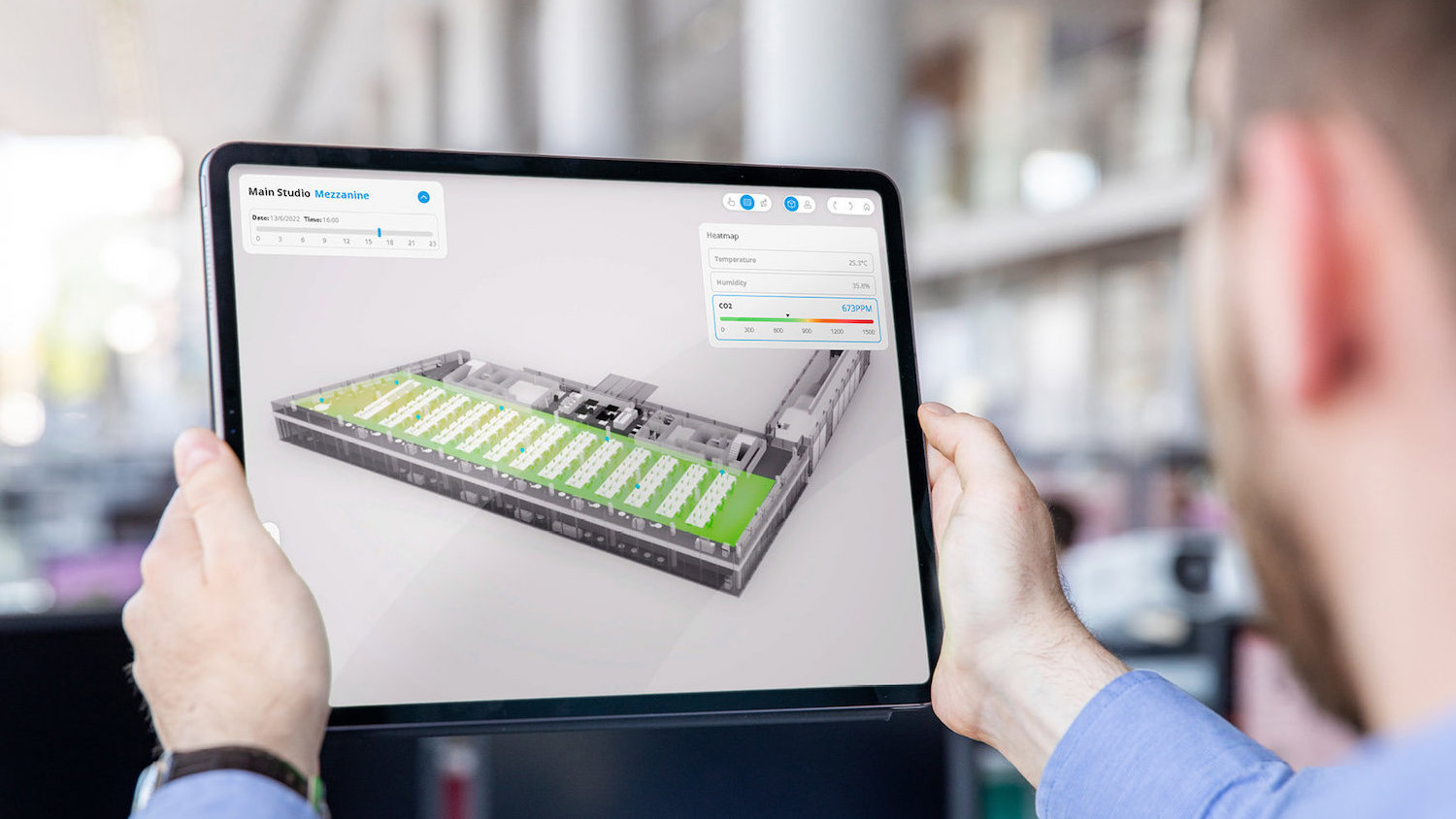

Adam Davis: We want to understand how our buildings perform during the whole of their lifecycle. That would include construction, operation, and even decommissioning. We’re obviously interested in the spatial and material record of the building, and also, therefore, of as-designed, as-built, operational models of buildings and building assets. We’re also very interested in the data that can be acquired through spaces in use – relating to things such as indoor and outdoor air quality, occupancy, and energy usage. Also, the sort of data you can gather from the functioning of building equipment.

All these things together can give you a useful ongoing picture of how your building is functioning. And you can then take that knowledge and bring it back into design.

At the moment, we’re exploring these opportunities with a digital twin of our campus in London. We have seven buildings that we occupy near our main office on the south bank of the Thames in Battersea.

So we have detailed geometric and business data models, which start as BIM models in many cases, verified through 3D laser scans of the premises. We have air quality sensors deployed throughout the campus and detailed information on energy monitoring. And we’re increasingly bringing online lots of information about occupancy around the campus.

We’re sharing the data with the facilities team and people who manage the practice and want to see it operate at its most efficient and productive. We have at least two years of historic data of aspects such as air quality and energy data.

“We have been looking quite a lot at technologies that exist outside the architectural engineering and construction industry, and trying to understand how these technologies can make our processes much better.”

What technologies are you exploring from other industries?

AD: We have been looking at technologies outside the architectural engineering and construction industry, and trying to understand how these can improve our processes. Many of the things we’re looking at are tied up with real-time performance-driven design from the gaming or film industries.

One example would be our Cyclops platform. Cyclops is a light ray simulator, with which we can make visibility calculations. We can do all manner of simulations related to solar phenomena: solar radiation, daylighting, a lot of environmental analysis. We use it when we design towers to understand their views of landscape and landmarks nearby, and for performance venues, where sight lines are critical.

By using this GPU computing, we can do tasks that might have taken hours or days to run, and we are running it now real-time. This means designers can pretty much have real-time analytics on how well their options perform.

Will you make this commercially available?

AD: Currently, it is in-house only, but we are looking at the commercialisation potential of some of these tools, and see whether it is worth our while doing it. It’s looking positive at the moment.

What new developments are you working on in augmented and virtual reality?

MT: We have been looking into augmented and virtual reality for a long time and have developed our own products in-house. At the moment, they’re not commercially available.

We’re not just using AR/VR so much as a visualisation tool, but as a design collaboration tool. During covid, for example, we used VR to carry out design reviews when everyone was working from home.

Glaucon, our AR/VR product, allows us to go onsite with a tablet or headsets and experience, for example, a virtual representation of the building on the site. We use these tools to facilitate collaboration, iteration and immersion. It has helped us focus on the human experience and engagement within the design process. We have used Glaucon for onsite review processes (such as planning applications), immersive experiences, and digital mock-ups.

“We have been researching the power of VR for more inclusive design: an open-source software that emulates visual impairments, released together with City University and UCL.”

And we have been also researching the power of VR for more inclusive design, as with the development of VARID, an open-source software that emulates visual impairments, released together with City University and UCL. We can use VARID to understand how visually impaired people see the space around them. And by being able to replicate any type of visual impairment, we’re trying to understand how we can use materials better to provide contrast, for example.

We are also building our own metaverse, which is a replica of our office that becomes our ‘sandbox’ for investigating different projects, being part of collaborative experiences, running digital reviews and meetings if we want to.

What would your teams use the metaverse for?

MT: This is an experiment. We might want at some point to introduce clients to a design virtually and they can be in a meeting with us in a virtual space. Like all experimentation, it might be something that takes off, but it might not. That’s the nature of R&D.

AD: One of the interesting applications for metaverse and digital twin applications is in training – putting people into an immersive experience that accurately reflects a real physical space, and asking them to perform tasks.

Why does Foster spend money developing its own applications? Is what you are doing very different to what is commercially available?

AD: For a number of our key products, we looked first at commercial solutions in the market. And in every case, we were able to identify a very clear value to developing our own. In many cases, we’re delivering this technology at a fraction of the cost that competing commercial solutions would charge us for doing similar things, or sometimes for doing less.

MT: We are not looking to reinvent the wheel. That is a waste of everybody’s time. All the applications we have developed do not exist commercially. Or, if they exist, they’re either too expensive, too difficult to customise, or too slow.

With the Cyclops platform, for example, commercial software exists that does what Cyclops does, but it’s orders of magnitude slower, so it’s not real-time.

What technology is going to have the most impact on architects?

“All the products we have talked about are creating their own data. And data is what drives anything around AI.”

MT: Machine learning and AI are going to completely reinvent the way that we are working through our design processes. And that is a change that is not going to happen in 10 years, it is going to happen much, much sooner. The transformational potential of this type of technology is immense.

But all the products we have talked about are creating their own data. And data is what drives anything around AI. So we think that all these things are somehow interrelated and will work together in the future.

AD: A close second ‘most impactful’ technology would be the extent to which all our work is networked and interconnected. In the metaverse and other applications, you’re seeing avatars of our colleagues sharing a virtual space in real-time.

And we’re also seeing the same thing happening in CAD and BIM applications, so that increasingly you can see the virtual presence of colleagues in real-time. And I think that is making a huge change to the way we work.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.