Work on the flagship Edinburgh St James project has been able to keep moving during the coronavirus lockdown thanks to digital collaboration

- Client: Nuveen Real Estate

- Lead consultant/technical architect: BDP

- Main contractor: Laing O’Rourke

Despite the lockdown forcing the suspension of onsite activities for 12 weeks, work still continued apace behind the scenes on the £1bn Edinburgh St James project, a key development for the city. Digital collaboration gave designers, engineers and contractors an opportunity to seize something good from the crisis.

This approach meant that it was business as usual for design development and coordination for the project team during lockdown.

As a result of the restrictions on site, designers and engineers have relied more heavily on digital collaboration tools, and the use of Building Information Modelling (BIM). Integrated virtual design and construction solutions are also being developed to be used end to end, from project concept through to commissioning on what is arguably the most complex building project underway in Scotland.

BDP Glasgow Studio is the lead consultant and technical architect for the design of Edinburgh St James, Nuveen Real Estate’s development, and is delivering the master plan as part of the Laing O’Rourke construction team.

Chris Hughes, architect associate, BDP Glasgow Studio, has worked on large projects using BIM for the best part of a decade, and he has seen a noticeable development in the size, scale and complexity of projects.

“BDP’s BIM working practices were progressively refined over a series of projects gradually increasing in scale and complexity. Silverburn shopping centre phase 3 in Glasgow, completed in 2015, was the final step in refining this process and validated that a large-scale shopping experience for the 21st century could be designed and delivered using the fully integrated BIM environment,” he says.

Information sharing

“This focus on a collaborative working environment with all information being shared digitally was the perfect experience needed for the larger and more complex project at Edinburgh St James. [Also] the great strides made over the last decade to refine working practices in a BIM environment are ideally suited to how we now need to work to within the social distancing protocols,” Hughes adds.

Edinburgh St James is in the final stages of delivery. The supply chain is in place and engaged, and construction is underway across all areas of the development.

Chris Hughes, architect associate at BDP Glasgow Studio

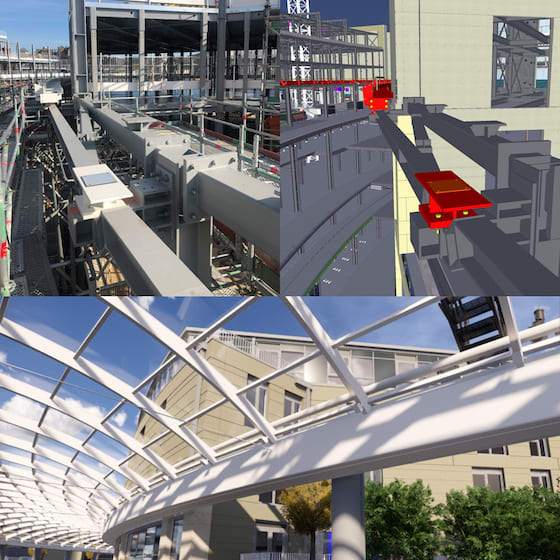

The way BIM is being used is part of a process that allows all the project partners to collaborate. The 3D model of the site is being used in real time. All parties are sharing a digital process and using the model as a virtual representation of the physical complex of buildings to validate construction processes, sequencing and assemblies long before materials arrive on site.

Hughes stressed that he is not referring to the use of twinning in the usual sense at the completion of a project: “The Edinburgh St James team has created a virtual simulation of the site, fusing Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA) grade model contributions, design intent models and point cloud survey data, to create a virtual representation that contains as retained, as built, as fabricated and as proposed information.

“This virtual representation is reviewed remotely by all parties, thus allowing emerging proposals to be interrogated and tested in three dimensions before further fabrication takes place. We have clear process and guidance, giving confidence in the resilience of the digital strategies we have in place. The complex model also facilitates virtual inspections, thus avoiding the need to physically visit the site. The project employs a cloud-based virtual reality capturing system, similar to that used in Google Maps. This allows users to interrogate the sequence of construction works.

“We can all sit at home and understand and track elements through a time sequence, from seeing a stone panel at the factory for inspection, seeing it delivered to site and its final position. We can also look at plans that show the detailed instructions used by the contractor on how it is assembled and installed.”

Video conference engagement

Engagement with all the stakeholders is an important part of BDP’s approach. The team has replaced site and face-to-face briefings with regular video conference updates and constant working on the model. Each of the team is responsible for one area of the building, and this means they have full knowledge of it. This one point of contact is helpful for the contractor and main client.

Laing O’Rourke has an in-house DFMA-based supply chain and BIM capabilities that use fabrication data from the model to drive an offsite manufacturing process. The model allows the creation of design intent, to develop into worked up design proposals to specialist subcontractors. This process also allows close collaboration between the UK team and elements of the supply chain based overseas. The systems are all in place from an early stage to enable detailed design and coordination to be undertaken remotely.

Site model of the galleria roof

Hughes comments: “I am an architect who enjoys designing with a digital model. But the model is only as good as the input. The beauty of BIM is that is simply a template for all types of styles of working. It allows for those who prefer drawing to have their ideas included within the model. On virtual calls, we can all comment on the model and add comments, and each time it is updated in real time. The design intent is intact, and any errors can be viewed and changed.

“At Edinburgh St James, while onsite works ceased, design, coordination and elements of offsite manufacturing continued. We also enhanced this work by using the concept of a digital twin as another innovative solution. The timeline for delivery can be established and order of works created. Meanwhile, the client can use the model to view the progress of the design remotely, and offer other suppliers or end users the opportunity to use VR to walk around the space and determine their own plans for the fit-out and completion.

“The phrase digital twin as used at the completion of a project is a tool that allows you to know the story of the building, and you can then use this knowledge to predict outcomes for energy efficiency, for example.

Cloud point surveys

“We are extending its use to relate to works on site to the design progression. The regular cloud point surveys from site and supply chain models of fabricated materials can all be connected back to the twin digital model. For instance, at the key interfaces between the retained parts of the scheme and the new build, we fuse point cloud surveys with DFMA information from the precast panels installed. We also consider CAD/CAM information from the glazing supply chain, fabricated but not yet installed, to refine design intent solutions.

“In a new world of construction where remote working is necessary, the digital twin becomes the one the designers and main contractor use to develop solutions such as design quality, precision and durability, at the same time seeking to minimise the impact on elements that are existing, fabricated and already in place.

Hughes concludes: “What we do know from working on Edinburgh St James remotely is, we are not hanging up our hard hats yet as there is always a place for us on site, but we recognise we have established real collaboration and progress using digital platforms, and this will play have a key role to play in the new world order.”