As the government announced its intention to prioritise offsite construction across its major capital building programmes, we catch up with Jaimie Johnston, head of global systems at Bryden Wood, who is in the vanguard of Whitehall’s digital transformation of designing for manufacture and assembly.

Tucked away in the Budget’s Red book was a paragraph with huge implications for the construction industry.

“Building on progress made to date, the Department for Transport, the Department of Health, the Department for Education, the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of Defence will adopt a presumption in favour of offsite construction by 2019 across suitable capital programmes, where it represents best value for money,” the chancellor said.

The intention was reiterated yesterday (December 6) in Transporting Infrastructure Performance, a 43-page document from the National Infrastructure Authority setting out plans to change the way infrastructure is planned, procured and delivered.

Though it might have come as a welcome surprise to much of the sector, for Jaimie Johnston at Bryden Wood it was a public affirmation of the practice’s biggest and most ambitious project to date.

He is currently leading a team in the Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) strategy for the new prison estates. This will see the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) spend £1.3bn updating its estate with six new prisons across the UK.

DfMA is an approach which facilitates the adoption of more advanced, manufacturing-led (as opposed to traditional construction) processes in the delivery of assets.

The 10,000 new jail spaces will be created by 2020 and will replace existing prison accommodation. £100m East Riding prison is the first to get the green light. The 1,000-capacity jail is planned to be built on 21 hectares of land to the west of the existing 600-capacity high security prison.

Though Johnston isn’t at liberty to talk in detail about the MoJ strategy which also involves The Manufacturing Technology Centre in Coventry, the programme represents the cutting edge of thinking articulated in the Budget – reducing costs and improving efficiencies by integrating the design process and compressing the delivery model. Components will be designed to be rolled straight off the production line.

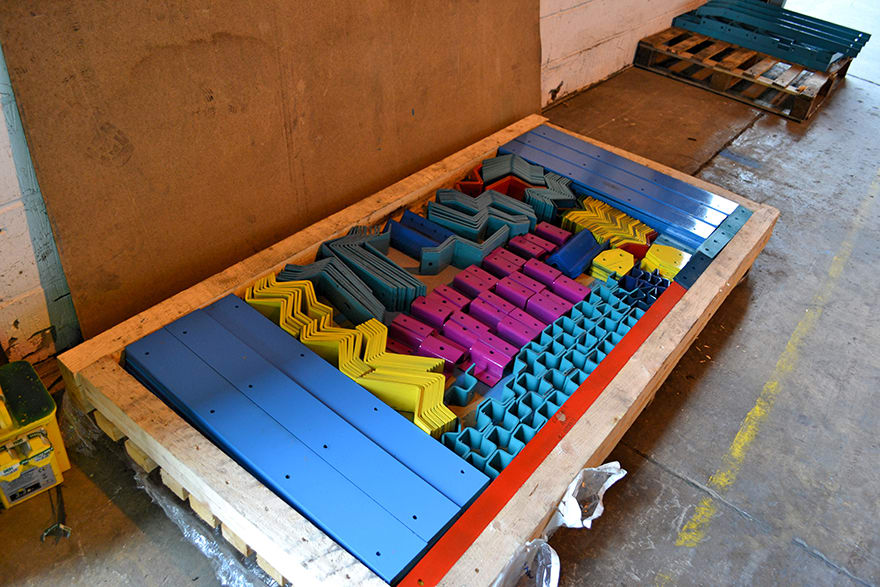

Bryden Wood’s “Factory in a Box” system for GSK

Costs of offsite manufacture have constantly struggled to be competitive with traditional construction, but mass production, which such a large programme allows, will turn this notion on its head claims Johnston.

“BIM in itself is an enabler. But If we are to meet government 2025 targets for productivity gains and cost reductions we will have to come up with a rapid low-cost way to do so,” he says.

He also dismisses the idea that offsite equals unimaginative architecture: “Having factory fabricated systemised buildings doesn’t mean you have to compromise on architectural quality. A kit of parts can make a good building or a poor building.”

Johnston is part of the Digital Built Britain team and recently wrote the report “Delivery Platforms for Government Assets: Creating a Marketplace for Manufactured Spaces”, which concentrated on a blueprinted digital process for buildings, and then followed this up for infrastructure.

These blueprints have been adopted by Digital Built Britain as the key articulation of the government’s aspiration to adopt a more manufacturing-led approach to construction.

Johnston says that part of the strategy is that more of the work could be carried out automatically: “Elements that were repeated such as gantries, you could easily teach a computer to design this. So, the work is not designed, but rather programmed.”

People doing that work in Bryden Wood are not engineers, but more likely architects, product designers or mathematicians writing rules for where gantries go in highways. “You can survey existing road systems using point cloud surveys and apply a basic series of rules,” says Johnston.

A mould CNC milled directly from a digital model

In fact, of the 190 people the firm has grown to, a quarter are non-traditional professionals. “The lines are blurring, even our architects have more knowledge about structural engineering and M&E design.”

Since the practice set up 23 years ago, DfMA has been its preferred modus operandi. It adopted software which would enable designers to provide a blueprint for the fabrication process long before BIM entered common industry lexicon.

It brought in software from other industries, employed its own engineers and even built its own factory to fulfil its ambition of delivering efficiencies designing building for manufacture and assembly.

These techniques have been implemented on a number of large projects such as London Heathrow Terminal 5, Terminal 2 and major frameworks for clients including GlaxoSmithKline, the Metropolitan Police Authority, the Ministry of Justice, London 2012 Olympics Athletes’ Village and on the Circle rollout of private hospitals.

Bryden Wood’s “Factory in a Box” system for GSK, which centres around the principle of rapid, safe site construction delivered through composite DfMA “components” that can be shipped out of Europe or procured locally depending on the availability of local, capable construction infrastructure won it much applause is perhaps its most well-known incarnation of this philosophy.

While prefabrication is often labelled as more expensive way of approaching design and delivery, Johnston dismisses the idea: “We’ve been in business for nearly 23 years and we’ve grown enormously. We wouldn’t be able to do that if we were uncompetitive and clients were unhappy.”

So how did it all start?

From the day it was set up in February 1995 it was with the intention to adopt design for manufacture and assembly. I was the very first employee and started soon afterwards. We wanted to be different to traditional architects. For us, the construction model was broken. The need to improve productivity and efficiency through more integrated working was a central theme of the Egan report of 1998. That report was a really good articulation of what we were set up to do.

We asked how other industries managed to make their products better and better – faster and cheaper to produce and be more reliable.

A “colour wheel” shows the breakdown of components in a recent Bryden Wood project, showing which are client-specific DfMA, which are existing products from the supply chain and which are site supplied

We realised that to be totally integrated with others we had to have our own engineers in-house and brought in structural and M&E engineers.

All the projects we do are as an integrated design process. Over the years we designed numerous buildings, but found the supply chain wasn’t in place to manufacture them, so we often had to set up our own factory. We had a factory in Andover for eight years, but the size of the projects got too big to build them.

Do you think you were ahead of your time?

Integrated design has certainly been slow across the industry, but mandating BIM Level 2 in 2016 has now started to integrate that process. But adopting Level 2 BIM won’t deliver the 2025 targets of efficiency and productivity, set out once again in the Sector Deal including cutting the time taken in construction products from beginning to end by 50%.

But BIM will become an enabler to drive greater integration?

We are finding more and more clients are willing to look differently at the process and don’t want to stop at BIM. When we’re bidding for projects, it’s certainly not enough to say you’re BIM enabled, it’s no longer a differentiator.

So, do we have the holy of grail of increased productivity in our sights?

The fact that the government is taking the low productivity in construction very seriously will be a great driver for change.

Construction is a very fragmented supply chain. In industrial processes in other sectors there is far greater integration. In two-stage D&B, the common route to procurement of building work, is not set up as integrated teams. Financial incentives are often not there either.

Bryden wood is short-circuiting the traditional contracting model and reducing some of the layers that add cost – everyone has to make a profit.

We’re designing components and we talk directly to the manufacturer – we can do that, it’s a very compressed way of doing things, but clients can struggle to accept that.

They still want to have a Tier 1 contractor in place. But in my view the role of tier one contractors has to change dramatically – they need to become assemblers – and provide logistical support.

Making quite a bold statement when we set up – but the fact is we have 200 people now – our client list enviable and the industry generally more enlightened it’s not such a lonely place any more.

We’re also prototyping a house based on DfMA which we hope to reveal in Q1.

What about machine learning and AI?

Designers need to accept that artificial intelligence and machine learning are coming, the imperative is the need to increase productivity.

Companies like the serviced office provider WeWork are using algorithms to optimise their assets. For example, they use them to work out the optimum number of meetings rooms in their developments to squeeze more value out of their assets.

If these tools lead to more effective layout, designers can spend more time on their creative energy.

How is all this development work at Bryden Wood funded?

I’d say we’re very entrepreneurial. We invest in R&D – claim tax credits – and develop innovative processes in parallel with our own projects – and then deploy on projects. Many companies are simply missing out on this opportunity.

We are finding more and more clients are willing to look differently at the process and don’t want to stop at BIM. When we’re bidding for projects, it’s certainly not enough to say you’re BIM enabled, it’s no longer a differentiator.– Jaimie Johnston, Bryden Wood