Adopting a kit of parts is all about enhancing design quality, says Dale Sinclair, head of innovation at WSP.

A focus on driving efficiency and quality in the procurement of buildings is leading many designers and clients, including government departments, to turn to Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA).

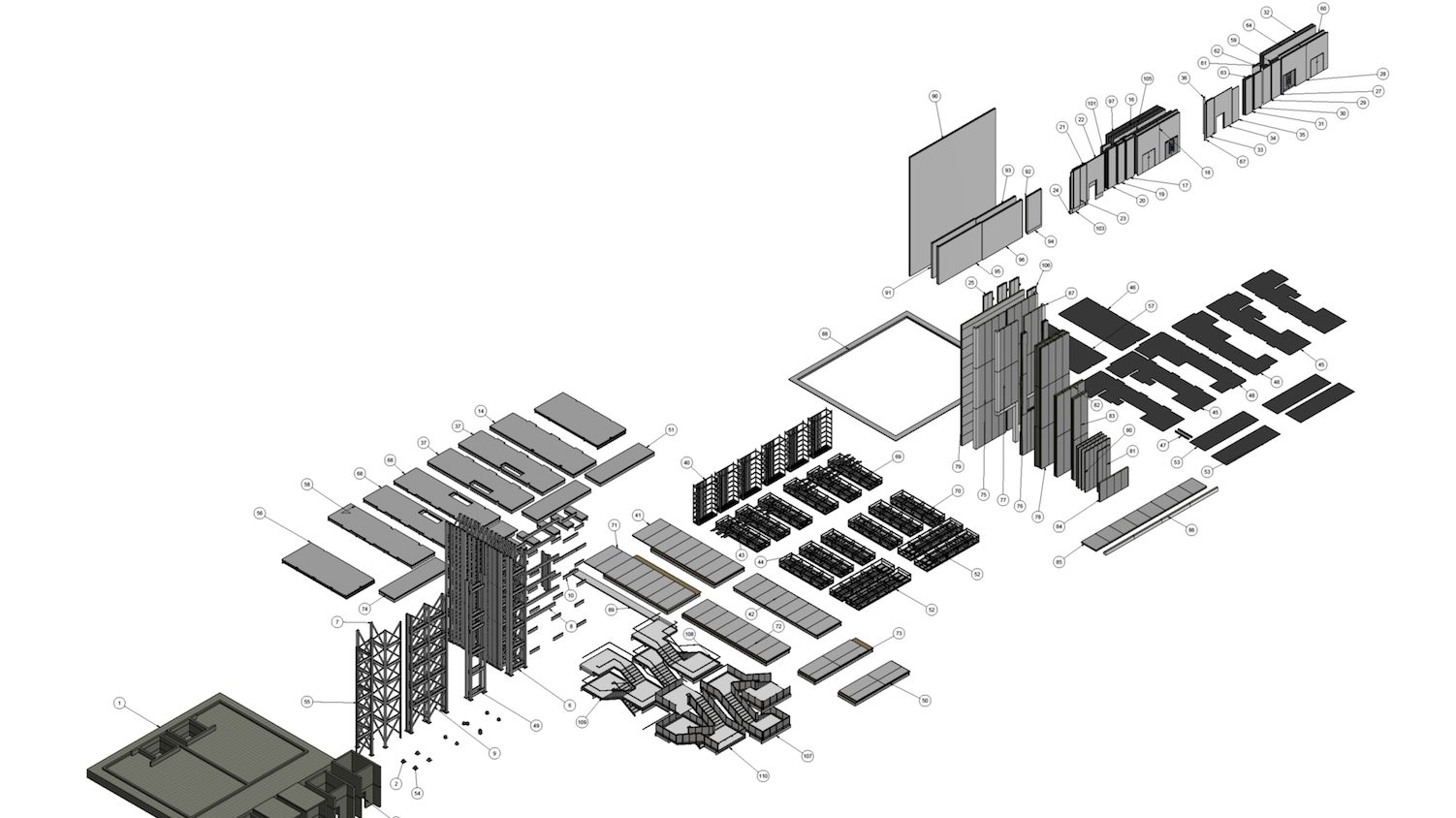

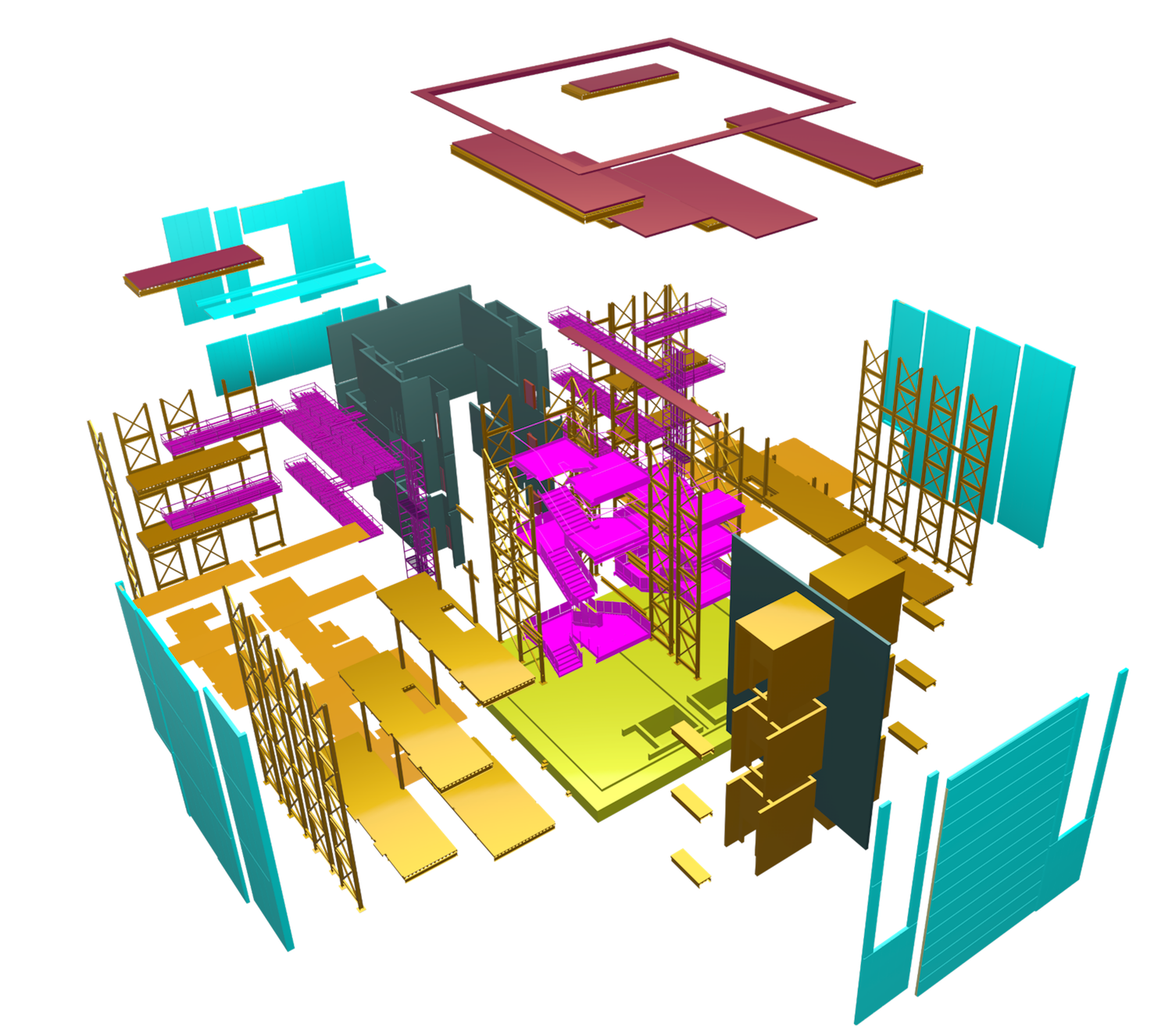

At the heart of this approach are platforms – or a kit of parts – made up of digitally designed components that can be used across different built assets, such as schools, clinics, hospitals or offices. The aim, says the government, “is to drive a new market for manufacturing in construction, and to provide a stable pipeline of demand to give industry the confidence to invest in new products and manufacturing technologies. This will deliver greater efficiency through economies of scale and add value by providing businesses and public services with infrastructure that performs better over its lifecycle.”

The global professional services consultancy WSP is among the firms that are driving progress in this field through a range of digital construction methods to support the design and engineering of complex projects.

In January 2022, it recruited Dale Sinclair as head of digital innovation within its UK property and buildings business. Sinclair, a pioneer in the development and adoption of BIM, is a specialist in using digital tools and solutions to optimise the design, management and computational delivery of large-scale projects in the built environment. At WSP, he works closely with the firm’s net-zero, digital services and MMC experts.

“The opportunity in shifting to manufacturing is incredible, because you can put half a million people into stable manufacturing environments – and therefore think about things quite differently.”

Doing things differently

Sinclair says his role involves trying to illustrate to clients that there’s a very different method available to make buildings, “which in a sense is quite similar to what we’ve been doing for 100 years, but in other ways it is a paradigm shift. Everything from the planning process to the supply chain, to building merchants – everything is geared to construction. So trying to shift away from that is not a simple process.”

He says the opportunities for creating more buildings in factories rather than simply on site have huge positive implications for the workforce. “If you take 30% of UK construction output and push that into the factory, you instantly create an industry that’s bigger than the British aerospace industry. If you take something like 20% of the construction output and push that into factories, you’ve got something like half a million people.

“So the opportunity in shifting to manufacturing is incredible, because you can put half a million people into stable manufacturing environments – and therefore drive social value propositions, and think about things quite differently.”

Sinclair adds: “It will take a long time for this to happen. But the momentum’s there, and we’ve got lots of clients that are trying to leverage that, including some abroad. There’s a huge demand to change the way we make our buildings.”

So how exactly is WSP going about it and what are the benefits for its clients?

BIMplus: What are your priorities at WSP?

Dale Sinclair: My title is head of digital innovation, but it’s almost like a holding title, because for me it’s just a proxy for doing things differently.

We’re seeing lots of demand from clients who want to decarbonise their buildings, and want projects delivered faster and cheaper. We’re trying to help them, and we’re making good progress.

What we’ve discovered in the last two years is that there’s a huge demand for kits of parts, which is a system that allows buildings to be replicated efficiently and cost-effectively.

Design has become more complex in recent times as we try to use offsite techniques to drive down operational and embedded carbon – we call it the ‘new complexity’.

So part of what we’re trying to do is see how we can take some of the complexity out of this process, to make it simpler for clients to make decisions. A lot of what we’re doing is about simplifying decision-making processes.

Do we really want our built environment to be full of repetitive, look-a-like buildings?

I think that misses the point. It’s not about taking design quality away. If anything, by doing this we can put more emphasis on design quality, because we’ve simplified the design process.

There are two paths we can see happening in construction right now. One is ‘optimised traditional’. That’s making what we’ve been doing for 500 years a little bit better. But I believe we’re on the cusp of a true paradigm shift in how we make buildings, and do them faster, so that they’re using less carbon.

That’s what’s really exciting about the projects we’re doing just now, that very different way of designing – more akin to product design than traditional design for construction.

Can you give me an example?

A lot of our projects are confidential at this stage. But some of the projects that we’re looking at, we would traditionally construct them in six months, but now we’ve got projects where we can put buildings together in a month. So we’re really gearing up a new methodology.

Some are simpler typologies, but we’re also doing residential, as well as schools, data centres, and others. So it’s not necessarily simplistic building types.

Are you coming up with kits of parts for individual repeat clients, or kits of parts you can use across your client base?

We’re doing both, but primarily we’re doing kits of parts for clients who are doing the same typology numerous times. That’s where it becomes interesting, because the goal is how much effort can we take away from a single project into a programme.

The reason, to date, why the industry’s not doing more in the factory, as opposed to taking lots of small things to site, is cost.

And the reason that it’s more expensive to go offsite is the way that we’re still putting things into the factory in small batches. Take a toilet pod. We design it, it has to go to a contractor, who puts it out to tender, someone wins that, we get shop drawings and it’s made in small batches. But why can’t we have a toilet pod as a commoditised element, that’s configured in the same way I might buy a car?

Looking at products ranging from toilets, baths, ironmongery, doors, or even sheets of plasterboard, the future as we see it is around a whole new generation of bigger commoditised products that can be purchased from catalogues. And the toilet pod would be a perfect example of that.

I can go on Ikea’s website and configure a kitchen, and have it by the end of the week. But there’s not a single website in the world where we as architects can go and configure a toilet pod.

So there are lots of different parts of the building that we can turn into products. I would call that commoditisation. But that’s where we see the future – much bigger pieces of a building that you can purchase and configure.

And through standardisation, you can push down costs, because the manufacturers have a more stable catalogue that they’re working from so they can make the factory more efficient.

Dale Sinclair

Sinclair joined WSP from Aecom where he spent eight years, most recently as director of innovation. He has authored numerous books and articles covering this field, including Assembling a Collaborative Project Team and RIBA Plan of Work 2013 Guide.

He was previously RIBA vice-president responsible for practice and profession, a RIBA trustee and councillor, and is currently on the board of the Construction Industry Council and chairs industry groups at the Construction Leadership Council and British Standards Institution.

We’d love it if we could get some clients to aggregate content. So, if we could take three clients and say, “you’re all using similar elements, how about we take those elements from a common catalogue that you can all use?” We’re really trying to work towards economies of scale.

Is this WSP acting in an architectural capacity rather than an engineering capacity? Or is it a joint thing?

It’s a joint thing. For a lot of the projects we’re working on, we’re working with external architects – quite a wide range of architects. But certainly it’s us driving the multi-disciplinary nature.

And with the kits of parts we’re doing, we are seeing a shift away from mono-disciplinary modelling.

How far down the line have you got with this?

We’ve got projects going to site this year, and they will be completed later in the year. We’re working with seven clients, and that’s allowing us to hone a more stable methodology that we can use on our next generation of projects.

Even with getting just two or three buildings to come together, and standardising what’s in those buildings, you’d be amazed at how much more efficient things can be.

We all think we know what offsite manufacturing is, because we’ve all created bespoke facade systems, or whatever it might be. But this needs much different rigour and discipline than traditional design.

And the more we do this, the more clients are really beginning to understand. We’ve got one client that’s doing several hundred buildings that are the same across a programme. And they’re realising the opportunities to create unique architecture on individual sites, but at the same time drive economies of scale through looking at how the buildings come together through a factory approach.

What other elements are you looking to standardise?

Most of the residential clients are using volumetric, which has had mixed results. The shift to volumetric has been fantastic in trying to move the residential market in particular away from construction into factory-based solutions.

But there are several reasons these companies are finding it difficult to implement. One is not enough standardisation: there are too many options being pushed through the factory. Another is overcapitalisation issues. Another is that factory slots are being missed because of the planning process.

We have a couple of clients now doing what you could call flatpack kits of parts. So instead of being volumetric, we have got lots of flat elements coming to site. And in that vein, we’re starting to look at different ways of defining how those elements come together.

“We all think we know what offsite manufacturing is, because we’ve all created bespoke facade systems. But this needs much different rigour and discipline than traditional design.”

Are you working with particular manufacturers?

On the whole, no. We are now modelling to a fabrication level of detail, but that’s really trying to work around agnostic solutions. All of our clients are keen to have supply chain resilience. So we try to create that in what we do. So we can work with specific manufacturers, but we also try to create new products that can be tendered to a range of suppliers.

How are you interfacing with contractors?

Some of our clients are looking to take more control of the supply chain, and see the contractor as an integrator. And we’ve had that integration role before, so it’s not a new idea – the contractor as an assembler, that’s the way some clients see it.

Other clients see collaboration with contractors and frameworks as the way forward. There’s no particular method that’s risen to the top of the pack yet.

The innovation we’re aiming to drive is not necessarily at the contractor level, because the tier one contractors we work with are incredibly nimble. The big shift is a whole new supply chain that can make much bigger things in the factory and then eventually commoditise, so we select things from catalogues, which have been optimised from a carbon perspective, and optimised from a cost and efficiency perspective.

How is it reducing carbon?

First is that we can be much more rigorous at the start in looking at what materials are optimal for all the different parameters – fire, acoustics, carbon, etc.

Second, by making things in the factory, we have significantly less waste. A huge amount of waste comes from construction, whereas we can optimise things in the factory.

And because we’re now modelling to a fabrication level of detail, we can align studs, and move elements to really eke out that efficiency. And then we can keep honing and honing and driving out waste.

Does it save design time?

Yes, significantly. But more importantly, we’re beginning to look at where we can add value using AI, and what we want to do as humans in the future.

For hundreds of years, we’ve been designing buildings heuristically, designing things intuitively. We certainly see a shift away to decision-making that’s much more robust in the future. If we can download the knowledge that we need to decarbonise our buildings, then we can really focus on the decisions that make a difference. So a shift away from heuristic ways of working into expert systems is all part of the work that we’re doing. And it’s all part of trying to make buildings much easier to create and put together.

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Ah, the eternal debate! It’s like we’re stuck in a time loop discussing this. But hey, let’s face it, humans have an insatiable craving for uniqueness and aesthetics. While private clients in retail and food services seem to grasp the benefitd of replicating designs & manufacturing of parts, the public sector, particularly local authorities, have this itch for crafting signature creations. Even if the intention is there to embrace a kit-of-parts at concept, the reality is that the endless tinkering often derails the efficiency train. Too much variation means the programme and costs spiral out of control, making the manufacturing process more of a headache than a solution