Having helped save 30,000t of carbon across 137 of its projects, Morgan Sindall’s carbon calculator, CarboniCa, is being developed to the next level to incorporate AI.

Tim Clement was working as a design manager in Morgan Sindall’s Midland’s office when he first had the idea of developing a carbon emissions calculator. That was in 2017, when he had joined a cross-company group looking at how the contractor could cut its emissions. The company had recently become the first UK contractor to sign up to the Science Based Targets Initiative, the scheme for corporates that helps them set targets and measure their progress.

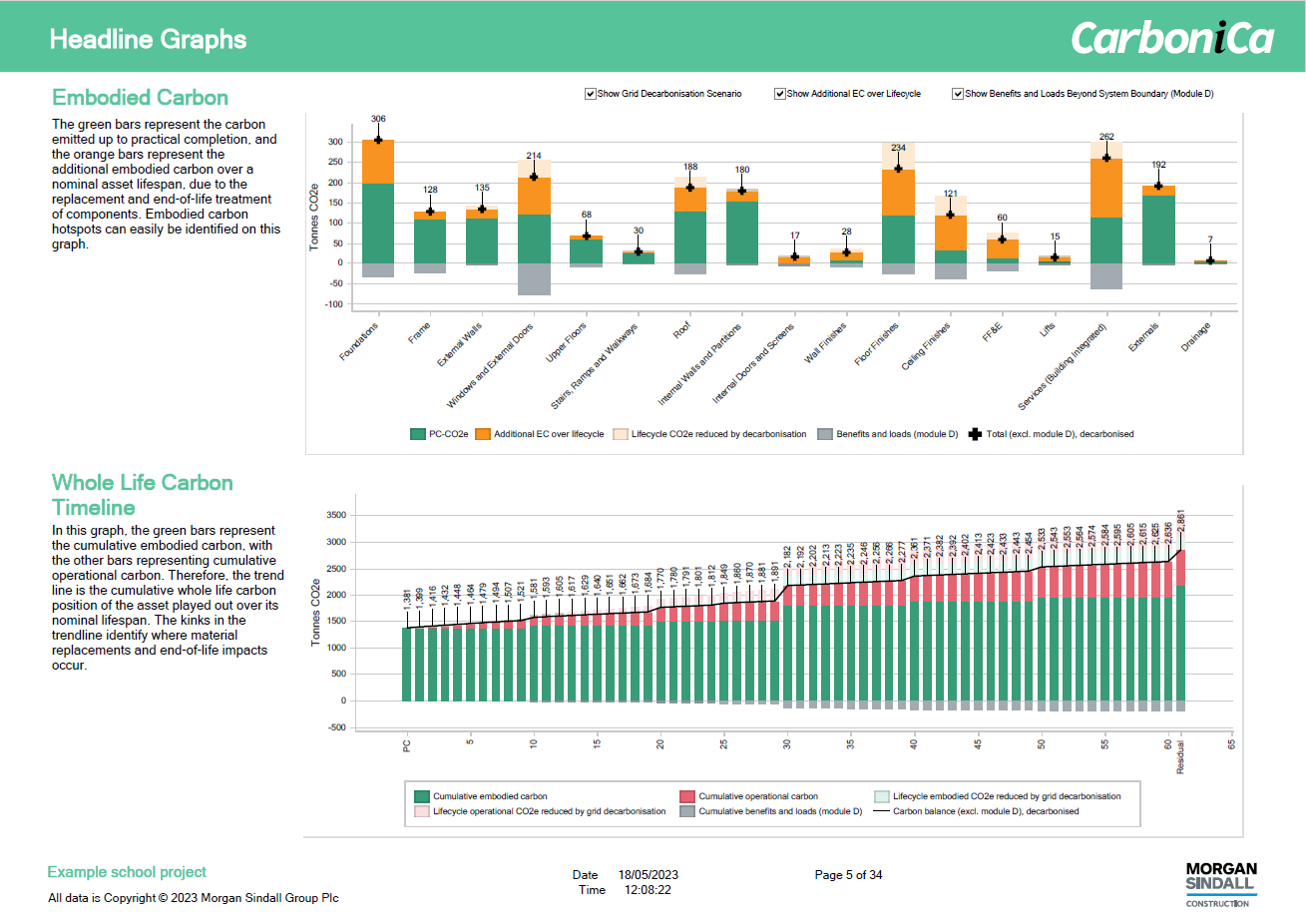

“I’d previously worked on a scheme where we’d conducted a whole-life carbon assessment of a building – and I could see that we would struggle to reduce emissions if we did not know how to measure them,” he says.

Clement worked on the idea of developing a measurement tool based on the RICS methodology for nearly two years while doing his day job. Then covid hit.

“It’s very much a contractor’s tool. Producing accurate information relies on the input from the supply chain and product manufacturers, and we have those relationships.”

“We started to see a sudden uptick in customer demand for measuring the embodied carbon of the materials used in construction of a building, not just the emissions during operation, so the tool became more investible and enabled us to turn it from an Excel spreadsheet into a modern web application.”

During this process, Clement took on a new role, leading on decarbonisation across the Morgan Sindall Construction business, including the development of the new web-based tool. It was validated by Arup, and in October 2021, CarboniCa was launched.

Since then, the tool has been used on half of the company’s projects and has helped save thousands of tonnes of carbon emissions. It is also being developed to the next level with the help of £1m of funding.

BIMplus: How much is CarboniCa used across the business?

Tim Clement: Morgan Sindall has a big commitment to innovation and sets out its stall to do business in clear, open ways, promoting transparency where possible throughout our industry. We have voluntarily reported on our environmental and social performance since 2007, and the ambition to lead the way on sustainability has only got stronger since then. That said, Morgan Sindall is decentralised, and in the construction division we have multiple local offices across the UK. So whenever we roll out a new tool or process, it takes a little longer to implement and train people than it would in a centralised business.

To our surprise, within a year, 50% of our projects were using CarboniCa on their project, or signing up just to give it a go. We launched an initiative called the 10 Tonne Carbon Challenge, which challenges teams to reduce emissions, and that has led to the greater use of CarboniCa. We’ve developed it extensively to meet BREEAM methodology and it’s been accredited by the BRE.

We’ve managed to save just over 30,000t of carbon through our 10 Tonne Challenge by using CarboniCa. And its insight has also provided many lightbulb moments for our own people, and for some of our customers as well.

How does it differ from other carbon calculator tools?

The difference with CarboniCa is that it democratises the measurement and reduction of whole-life carbon by putting it in the hands of non-experts. So it can be used by a design manager or quantity surveyor, or sometimes a site manager with input from designers and the supply chain. People are happy to use it as they see measuring carbon as a good skill to have.

It’s a web browser. It can be used on a laptop and tablet, but I think the screen on a phone is just a bit small. In terms of input, I would say 30% of our projects use BIM data to populate the project data. The remainder would start with the bill of quantities or cost plan, produced by the estimator. And then during construction, we’d use actual data for the high-carbon elements, like concrete volumes delivered to site and those kinds of things.

It’s very much a contractor’s tool. Producing accurate information relies on the input from the supply chain and product manufacturers, and we have those relationships. We conducted an exercise with the architectural practice Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios to compare tools and learn from each other.

Sometimes we might compare with calculations from other tools and realise that they may differ because incorrect assumptions have been made or they have omitted data, such as a site waste, site fuel, or made assumptions about the design which are inaccurate. Our data is almost always higher. This trend of underreporting has been reflected in the latest update of the RICS whole-life carbon standard, where a contingency factor needs to be included at earlier stages of the design to compensate for this phenomenon. We pushed back against this new requirement because we felt it didn’t apply to how our tool has been designed.

When your teams use it, where are they typically saving carbon?

When we generate a CarboniCa report, one of the pages is a material analysis, and it ranks every material in the project from highest carbon impact to the lowest. Top of the list is usually concrete, followed by steel frame, and PV panels are near the top as well. Aluminium cladding and raised access floors and sometimes plasterboard are often near the top as well. Often, reductions involve reducing concrete volume or looking at different mixes. If the frame is steel, it will be looking at procuring steel produced by an electric arc furnace for reducing the amount.

CarboniCa in use

Buntingford First School in Hertfordshire was the first net-zero carbon building for the county council and was designed to Passivhaus principles to improve air quality, reduce carbon emissions and lower the school’s energy running costs.

To help achieve this, the project team used CarboniCa to identify a number of carbon savings, which included minimising the amount of concrete in the foundations by reducing the number of piles and depth of the ground beam design, as well as mixing 50% of the concrete with GGBS, a low-carbon concrete alternative. The team also opted to use a timber frame in the design and HVO fuel was used on site during the construction.

The solutions delivered by the team amounted to a 203t reduction in embodied carbon.

Meanwhile, at its Victoria Road scheme in Brighton, where Morgan Sindall has built 42 residential flats for Brighton & Hove Council, it worked with supply chain partner Sigmat to find alternative solutions to the building’s structural frame, using CarboniCa to review the carbon credentials of the given options.

By using a lightweight steel frame rather than the concrete alternative, CarboniCa measured that there would be a 177t saving in embodied carbon at practical completion.

How is it developing now?

We’ve recently secured two rounds of funding to take CarboniCa to the next level. The first level was to develop an educational version of the tool, with Nottingham Trent University, which is relatively low value and will complete in May. The second is about to start [this month] and is an AI-led programme of work, which has attracted almost £1m of Innovate UK funding between us, Nottingham Trent University, and the software developer ConstructSys, which is based in Warrington.

Nottingham Trent University’s role is to develop the algorithms. Our role is to make sure it works from the customer’s point of view, so that it adds value. ConstructSys is doing the software development.

It’s a 12-month piece of work to embed aspects of AI/machine learning. We’re looking at using algorithms to go through all projects that we’ve used CarboniCa on where we know the data is of good quality. We have 100 projects that we have peer-reviewed the data for and which we are happy with. So having got this database, we can then model the embodied carbon to generate rough concept design quantities.

The idea is that a customer would be able to use CarboniCa to look at the carbon intensity of a project and how that would change with different options, such as using timber and steel, very early on. It’s a productivity piece of work and we received funding on that basis. It speeds up the first part of working out what the carbon impact of that project might be.

The second part of the programme builds on the existing functionality of the tool. Currently, based on the user input, it will provide a list in its output report of what to do differently to reduce carbon. So it will pick up whether it’s a steel frame, or brick facade for example, and then in a couple of sentences, ask the question: “Have you thought about considering this? Or this? Or this?” This new development will mean we can provide options on a more granular level for many more building elements, again saving designers and contractors much more time.

The funding has allowed us to appoint a product manager to work on the development full-time.

Is the plan now to make CarboniCa available commercially to others?

It’s always been our intention to share what we’ve created. We already licence it via one of our sister companies, Muse, so its consultants and contractors can use it. We’re always open to opportunities to share it, but we’re not a software company and that naturally limits our ability to support large numbers of individual users outside our organisation.

What’s in it for ConstructSys?

The benefit to them as an SME is that it will grow their AI capability, which would allow them to market themselves in that space. So, in terms of the product itself, it would remain a registered trademark of Morgan Sindall Group. But once the project is finished, it’s just a case of seeing the appetite in the market for the AI-enhanced product. And then we must think, what is the right way of serving that demand? Is it through us? Or is it another entity?

Don’t miss out on BIM and digital construction news: sign up to receive the BIMplus newsletter.