Finding it hard to grasp what open data means for the industry? The BRE and Generation for Change (G4C) embarked on a study to demystify the topic, and the BRE’s Daniel Skidmore has summarised the findings in this blog. The original article was posted here.

The UK is now becoming a much more digitised community, and data is being collected in a range of different ways. However, it is now important that organisations truly understand how to successfully analyse this data for improvements to be made. This article discusses how data can be used to inform decisions, and how opening datasets has the potential to drive economic, social and environmental benefit.

This article is based on a study carried out by BRE in collaboration with Constructing Excellence group G4C to investigate the potential for data in the built environment. The study looked to demonstrate the potential benefits that collecting, managing, analysing and even releasing data can have on a range of organisations within the construction sector.

Mining

Data mining is an analytic process which can identify patterns, relationships and correlations from within a dataset. This can also include looking for anomalies. For example, data mining can be used to spot anomalies when looking at any type of consumption (water, electricity, gas).

Mining can also be used to detect patterns within datasets. For example, if a site manager records all of the near misses witnessed on a construction site, it is possible that mining could be used to establish if there are patterns in the data. This would enable the site manager to identify the areas which are currently posing the highest risk, and put in place measures that could reduce this. This sort of analysis can help organisations to become increasingly efficient in everything they do.

Mapping

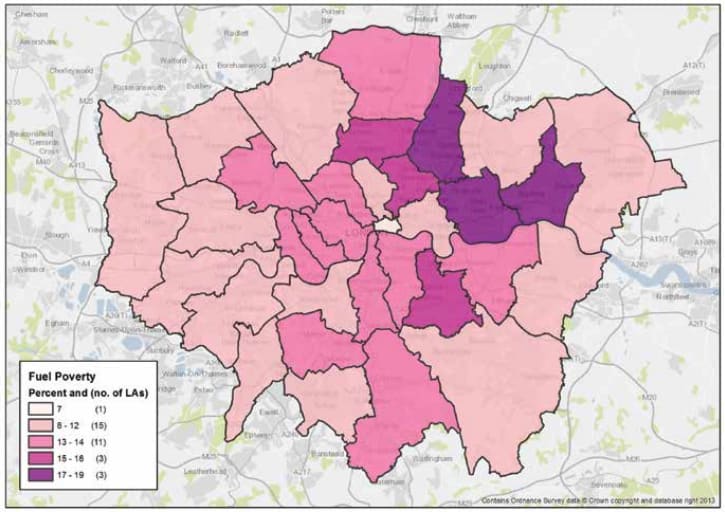

One of the most effective ways to utilise data is to map it. Provided you have geospatial data (ie data that contains a geographical location), it can be placed on a map. Figure 1 demonstrates how data regarding fuel poverty in London has been successfully mapped in order to clearly distinguish the most prominent areas.

Mapping is a particularly effective way in displaying data due to our familiarity with digital maps, such as Google Maps. People can quickly relate things to a map, rather than if the same data was portrayed in a spreadsheet. Mapping could be particularly useful in portraying information within the construction industry, due to its substantial interaction with maps and plans.

Figure 1: Distribution of fuel poverty in London Map based on BRE housing stock models and Experian data taken from the Cost of Poor Housing in London IHS BRE Press 2014

Mashing

The real power within mapping can be seen when you start to combine data sets – often referred to as mashing or crunching – to find correlations. For example, if you were to map data which demonstrates the percentage of waste sent to landfill on a range of construction projects throughout Scotland, it may appear that there is one particular location where landfilling predominates, rather than recycling.

With this one dataset it would be difficult to establish why this might be. However, if you were to combine this data with the locations of all of the waste recycling facilities within the surrounding areas it may become apparent that this location does not have a facility in proximity, and subsequently it is easier and cheaper for contractors in this area to just landfill their construction waste.

This enables you to combine datasets in an attempt to understand whether there are correlations between different variables, and allows measures to be put in place to overcome problems or spot opportunities for improvement.

Driving the release of open data within construction

A large amount of the open data already released has been done so by the public sector. There are clear visible benefits for the public sector to undertake its release. First, it provides transparency. By releasing data and information regarding a local authority, it demonstrates a desire to be open and honest with its inhabitants.

Second, by releasing data it provides developers with information that enables them to develop new and innovative applications which not only create economic growth, but can also provide wider benefits to society.

Another benefit that is seen by the public sector due to the release of data is the reduction in freedom of information (FOI) requests from the public.

It is these clear and distinct benefits which have made the public sector the forerunner in the open data agenda.

But there are also drivers pushing the release of private sector data. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is currently driving many large organisations (most notably clothing manufacturers) to publish data on their sustainability as well as their supply chain.

Another driver is when sharing datasets between companies can actually help to reduce a common risk. Chief Information Officer magazine demonstrates that insurers have been undertaking initiatives like this for many years in an attempt to combat fraudulent claims.

This could have similar benefits for organisations in the construction industry. By identifying high risk areas of a construction project (for example planning), it could be beneficial for companies to share data in this area to mutually reduce risk and improve efficiencies.

When discussing the topic of open data throughout this project, it became clear that people find it very easy to understand why a local authority would start to release its datasets. However, as soon as the topic changes to the release of private sector information, the argument loses momentum. People continue to remain wary of giving away information that they believe to be of value to potential competitors.

There is a perception that data is like a rare object and that once you have given it away you have lost all of the value you had with it. However, this is not always the case. Although releasing data can be of benefit to society, it can also have an economic benefit for those who release it. Getting people to discuss how innovation can arise from your datasets could be a huge commercial benefit, and could even be looked upon as free research and development.

Furthermore, by allowing completely different sectors (which are not hidebound by your industry’s current processes) to analyse your data, you may find uses which people internally would never have thought of.

Business models for releasing open data

The Open Data Institute, a not-for-profit company co-founded by Tim Berners-Lee in 2012, has undertaken great work to better explain the potential business models which can help organisations get value from releasing their data. The work concentrates on several business models, including freemium and cross subsidy.

The ODI explains that the freemium model involves an organisation releasing a sample dataset or tool for free (perhaps a small portion of their dataset), which in turn will create interest in a more in-depth product which has the potential to be sold (for example the entire dataset). By allowing people access to your datasets it enables them to understand the potential the entire dataset could offer.

This business model of using a sample to entice people to purchase more is a common approach, and within construction it is often seen within market research. For example, organisations often provide summaries as well as key insights on a particular topic in an effort to tempt people to purchase the full-price report.

There are alternative ways to utilise the freemium business model. Organisations can also release their data under a license which requires those who use it to openly share their findings. This can result in the development of new uses for your data that your organisation had never considered.

Alternatively, if a developer does not want to release their findings after using your organisation’s data, then they must negotiate with you to attain the data under an alternative licence. This allows the new licence agreement to be chargeable, subsequently creating value.

Another proposed model is cross subsidy. This is where alternative benefits can arise within your organisation from the release of open data. One simple benefit is that releasing data can be a great source of advertising. An organisation can attach a licence requiring anyone who uses their data to attribute their work in collecting it.

A further benefit can actually be additional business opportunities. For example, if an organisation which collects data on the efficiency of construction projects decided to release a number of their datasets, they would have the most knowledge and experience of using that dataset. This organisation could then offer a range of consultancy services to those looking to utilise the dataset.

Organisations need to initiate conversations surrounding open data, and start to understand the potential benefits that it could bring them, whether they would like to utilise open data that has already been released by other organisations, or they are thinking of releasing their own.

There is a perception that data is like a rare object and that once you have given it away you have lost all of the value you had with it. However, this is not always the case – it can have an economic benefit for those who release it.– Daniel Skidmore, BRE