- Client: Barratt London

- Lead Contractor: Barratt London

- BIM Tools: Autodesk Revit, Solibri Model Viewer, Tekla BIMsight

An informal approach to BIM, based on a “gentlemen’s agreement” between architect Patel Taylor and structural and MEP consultant O’Connor Sutton Cronin (OCSC), suited the “organic and fluid” approach taken to designing Lombard Wharf, a curvy 28-storey apartment block located on the Thames in Battersea, London.

The 16,421 sq m tower, due for completion in December 2017, is notable for its exterior of pre-cast concrete wraparound balconies, reminiscent of the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York, which create the impression that it twists as it rises.

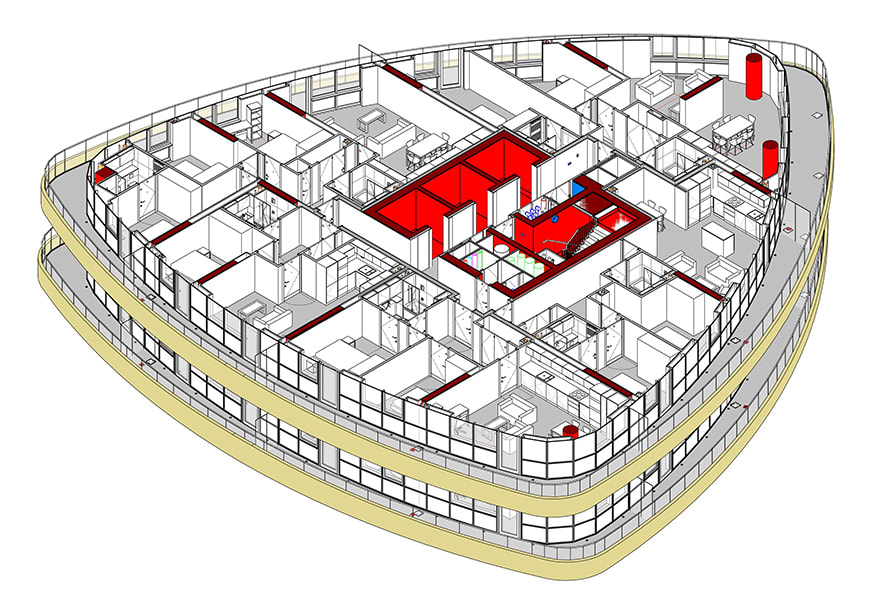

The building will feature 135 dual-aspect apartments and penthouses with a base featuring a double-height entrance lobby and shops spilling out onto a landscaped public plaza connecting to the Thames Pathway along the river.

Patel Taylor suggested the use of BIM to Barratt London, as the architect had emerged from a pilot BIM phase delivering two jobs using Revit. In addition, the architect felt that designing in BIM would help address the difficult site conditions and suited the programme of work for a stacked residential block.

The project fulfills certain requirements laid down in the BIM Level 2 definition, as the architecture, structure and MEP models are being federated in Navisworks, and Barratt’s document management system serves as a Common Data Environment.

However, a protocol-bound approach to BIM was rejected by the consultant team, explains Kieren Porter, BIM manager at Patel Taylor.

“We took the decision not to formulate a BIM protocol or a BIM Execution Plan, instead relying on a gentlemen’s agreement with OCSC. We felt that we didn’t need to go through the rigmarole of BIM responsibility matrixes, playing cat and mouse around a BIM protocol governing what aspects have to be completed when. Those things have an important role to play on bigger projects, with more players, but we wanted the process to remain organic, fluid and agile.”

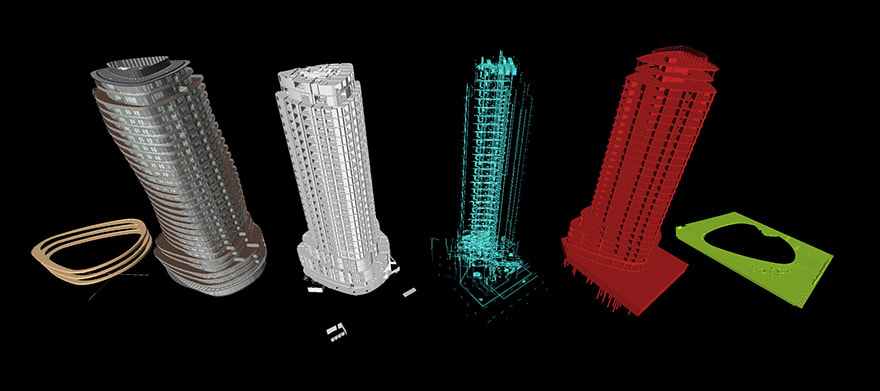

The architect produced separate Revit models for the exterior, interior and the site, which were federated with OCSC’s structural and MEP models in Navisworks to help speed up reviews and coordinate the design.

Subsequently, Patel Taylor’s exterior model was swapped out for a more detailed construction fabrication model, developed by precast cladding supplier Techcrete. The latter’s Tekla model was imported into BIMSight and Solibri Model Viewer using the IFC protocol.

“Seeing Techcrete’s fabrication model with actual building tolerances has been key for clash detection and avoidance,” says Porter. “We have a monolith of a precast balcony on every level, with associated structural load, insulation and cold bridging concerns, requiring really intricate details at the balcony and glazing interfaces.”

The architect produced separate Revit models for the exterior, interior and the site

Several offshoot design studies benefited from the decision to model in Revit. The exterior model was converted and plugged into glare analysis software, as part of planning conditions, to demonstrate that light reflected from the windows would not affect helicopter pilots landing at the nearby heliport, or train drivers following rail lines into Waterloo.

Given the geometric complexity of the exterior, with 28 floors that curve in different directions, this approach was considered much more accurate than developing an approximation that planners might find insufficient.

Revit was also used to develop iterative design studies resolving how to dig the six to seven metre-deep basement and install piles alongside the river.

Rather than have the OCSC team model every MEP condition in every apartment, a set of rules was set up describing how different conditions should be treated.

“We identified ‘pinch points’ where the condition had to be modelled, but OCSC didn’t have to create every light switch, plug and spotlight,” says Porter. “As a result, there will be occasions on site when we will have to resolve certain conditions, but that is preferable to having masses of unnecessary information in the model. We have tried to play to Revit’s strengths but not its weaknesses.”

The base features a double-height entrance lobby and shops spilling out onto a landscaped public plaza

Porter admits that the gentlemen’s agreement established with OCSC and the lack of a BIM Execution Plan for the project is posing some challenges as work gets underway on site. In cases where a new condition needs modelling, or a pipe has been uncovered that wasn’t anticipated, it has resulted in site managers wondering who they should call to resolve the specific aspect of the model, whether structural, MEP or architectural.

“In most cases this can be resolved through a simple five minute chat with a designer, which is far more amicable and sociable on a project than requiring a new edit and re-release of a document,” says Porter, who describes himself as a “BIM outlier” and not a fan of many of the structures set in place by the government mandate.

“Although there are merits to having everything set out and documented, so that people don’t have to worry about litigation and everything is squared away in contract, sometimes that approach can be obstructive. Technical experts and articles in the press make BIM seem daunting, I want to show that it is just business as usual and we can negotiate the hurdles as they come,” he concludes.

We felt that we didn’t need to go through the rigmarole of BIM responsibility matrixes, playing cat and mouse around a BIM protocol governing what aspects have to be completed when.– Kieren Porter, BIM manager at Patel Taylor