These days breakthroughs in 3D printing are never far from the headlines, but it still has a long way to go to reach its full potential. Tom Ravenscroft looks at what it offers in terms of onsite innovation.

For the past 10 years 3D printing has been threatening to revolutionise the construction industry, and over the last two years it seems to have been constantly in the press. Successive headlines have announced the achievement of numerous world’s firsts as the technology edges ever closer to the mainstream.

News from Madrid earlier this year of the world’s first 3D-printed bridge was followed by the world’s first house 3D printed on site in Russia.

Dubai has been leading the charge. In 2016 it completed what was claimed to be the first 3D-printed office – understood to have been created by Winsun Global, the international division of China’s 3D printing pioneer Winsun, in partnership with global architecture firm Gensler among others – and announced plans for the world’s first 3D-printed skyscraper.

Currently it is building a research hub for drone and 3D printing technologies.

At the opening of the office, ruler of Dubai Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum announced plans to print 25% of its buildings by 2030.

With so much hype and, as yet, so little real-life impact on the industry, it may be easy to ignore 3D printing as a fun gimmick that will quickly be forgotten. But what if it really is set to be a game-changer for construction?

For those who have not yet come across the term, 3D printing is the process of creating a three-dimensional object by laying down layers of a material in succession. On the scale of a building, the process has the potential to create extremely accurate houses, faster than traditional techniques, while producing very little waste.

Above: SOM’s AMIE 1.0 pavilion was assembled from 3D printed polymer components

On a smaller scale, it is a valuable tool for rapid prototyping and can create elements that cannot be made any other way.

The technology has been adopted in many industries, including aviation, and practical applications are now being explored for the built environment, with opportunities appearing for contractors and architects to take advantage of the digital innovation.

“3D printing is opening up new techniques and manufacturing methods that were not previously possible,” says Simon Hart, senior innovation leader for smart infrastructure at Innovate UK.

“Contractors should be looking to identify the potential to use 3D printing within their businesses,” he continues. “If they are not, they can be sure that their competitors are.”

But how are those in the built environment actually using 3D printing? One area where it is already heavily used is in model making and form finding – and this is providing a perfect test bed for architects to learn the technology.

Foster + Partners is one practice that is leading research into the process. “Our first 3D-printed model was made in 1999 for the mega structure on the Swiss Re model,” says environmental design analyst Samuel Wilkinson, an associate at the practice, referring to work on the City of London’s Gherkin.

“We acquired in-house 3D printing capabilities in 2004, and in 2011 we established a full in-house rapid prototyping suite equipped with state-of-the-art 3D printing devices. Eighty per cent of our models now use 3D-printed components.”

Apis Cor’s house was printed on site near Moscow in 24 hours earlier this year

Rapid prototyping allows the practice to make a series of design iterations for comparison, and also to make bespoke parts within a traditional model that would be too difficult or expensive using other methods.

It is now exploring the possibility of building full-scale structures – including efforts on a project to build a habitat on Mars and the moon using 3D-printed regolith – and is researching how best to advance the technology.

“We are also working with Skanska and Loughborough University to look at ways that we can 3D print building components in concrete, and with a large consortium including Autodesk and Cranfield University on large-scale additive manufacture with metal,” says Wilkinson.

Main contractor Skanska is serious about exploring the potential to incorporate 3D-printed components in its construction process. While various materials, such as plastic polymers and metal, can be used for 3D printing, Skanska has chosen to focus on concrete, as this is where it sees the possibility for the most real-life applications.

“Our main thrust is producing components that cannot – or cannot easily – be produced through regular methods,” explains Sam Stacey, its director of innovation and business improvement. “It’s difficult to put a strict time scale on it, but I would certainly hope that we incorporate 3D-printed components in one of our buildings within the next three years,” he forecasts.

As the technology evolves, organisations around the world are looking to upscale 3D printing to create entire buildings. “It is entirely probable that 3D-printed houses will be available soon,” hypothesises Brian Lee, design partner at US architectural practice SOM.

“3D-printed components will increasingly be made and assembled into larger projects, which will revolutionise the way in which the 3D printing relates to the architecture industry.

“As rigs and printers evolve and material matrixes are developed, other challenges such as structural cohesion and integrity, geometric capability, waterproofing, and dissimilar materials will need to be resolved at a faster rate.”

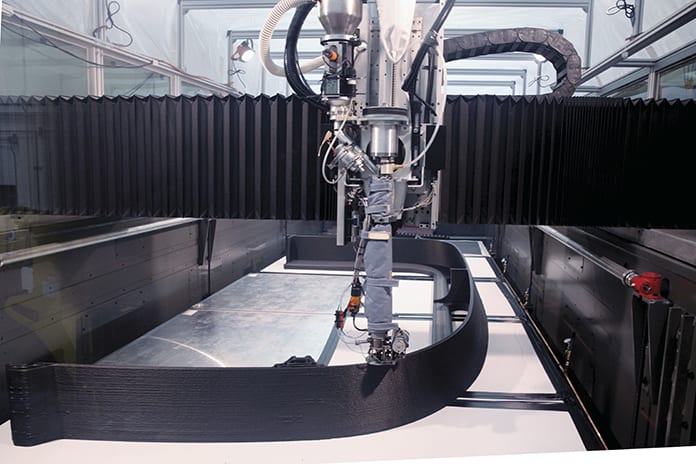

Printing SOM’s AMIE 1.0 pavilion at the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge Laboratory

SOM has been collaborating with the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory to investigate and develop 3D printing. One of the results of this research was the creation of the world’s largest 3D-printed polymer structure: a pavilion called AMIE 1.0. This was assembled from 3D-printed panels that act as exterior cladding and provide structural support, insulation and moisture protection.

Lee, the lead designer on the AMIE 1.0 demonstration project, is cautiously optimistic: “There is great promise for 3D printing, but we are still learning and evaluating its design potential, while seeking to optimise its effectiveness as a sustainable building method for the future.”

While the technology to create 3D-printed buildings now exists, this does not necessarily mean that we are about to see an Uber moment in construction, as there are still many barriers to wide-scale adoption.

“3D printing houses is realistic and can be demonstrated using today’s technology,” says Innovate UK’s Hart. “The take-up of 3D printing depends upon the economic benefit of its application. It has to be robust, reliable and repeatable in harsh environments. It also has to be simple to configure and use.”

With the technology developing quickly, there is potential for startups like US company Apis Cor to disrupt the industry. “We believe that over the next 10 years 3D technologies will evolve to the level where not only the walls, but each and every element of a building is constructed directly on site with additive technologies,” says the company’s CEO and founder Nikita Cheniuntai.

“Given the speed with which 3D printing evolves today, we will see the industry being completely revolutionised.”

A house in 24 hours

Apis Cor gained international exposure earlier this year when it successfully printed the first fully formed, onsite 3D-printed house in just 24 hours. Though he clearly believes 3D printing is the future, Cheniuntai understands there are still obstacles to overcome before he can start rolling out houses.

“While the technology is already capable of minimising expenses during the wall construction process, there still exist the formal barriers of obtaining proper permits and certificates before mass use of 3D printers in construction can begin,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Cheniuntai is already looking to push the boundaries. “While we are solving issues connected with regulations and market entry, we are also working on new equipment designs for performing other tasks – including 3D printers designed for high-rise construction,” he says.

Another early-adopting company is DUS Architects in the Netherlands. For the past three years, the practice has been engaged in a research project to 3D print a typical Amsterdam canal house. Unlike Apis Cor’s creation, it is being printed in components and assembled.

The first 3D-printed office was developed by the Dubai Future Foundation

DUS Architects co-founder and partner Hedwig Heinsman believes we are “close” to seeing 3D-printed houses appearing in cities, though perhaps not the UK at first. “In BOP [“bottom of the pyramid” or the world’s 4 billion poor who make less than $2 a day] countries, simple 3D printing could be very effective to offer large groups of people modest types of housing,” she suggests.

But it is in disaster areas that Atkins’ head of digital transformation, Neil Thompson, sees 3D-printed houses being initially rolled out: “I’d imagine printed homes would hit emerging cities with a need to grow fast. We may find ourselves one or two major earthquakes away – like the one we saw in New Zealand – from a 3D-printed city.”

However, it is not houses or even structural elements that Thompson sees offering the greatest potential. “I think the role of 3D printing in electronics is the biggest area of opportunity,” he says. “I can imagine a building that has mostly printed circuits. Saving hours of laying cables and wiring, while providing flexibility of the space.”

Related articles

- Bespoke designs, community factories and the rise of the citizen builder

- A Dubai drone lab in just three weeks

- A Tuscan dream that finally made its mark on the world

While the specifics of how 3D printing will impact on the industry remain unclear, some, such as Heinsman, believe it will change how we all work: “Ultimately, digital manufacturing will lead to a complete paradigm shift in the AEC [architecture, engineering and construction] industry,” she says.

“The industry is currently locally oriented, meaning businesses cannot simply be applied globally. The industry is not very demand driven and incapable of offering affordable tailor-made solutions. I see all this changing within a decade.”

Jacqui Glass, professor of architecture and sustainable construction and director of the Centre for Innovative and Collaborative Construction Engineering at Loughborough University, agrees with this timescale and believes 3D-printed houses will appear in cities within the next 10 years.

She says: “There are already prototypes in other countries, and signs of strong interest globally, but it may not happen in the UK first – surprise, surprise! Individual homes are a certainty – but they are likely to be the ‘Grand Designs’ ones first!”

While these one-off houses will only affect a small part of the industry, Glass sees printed components, such as the ones developed by Skanska, entering the supply chain in the near future.

Manufacturing components

“There will definitely be evolution as well as a broadening and market growth of the technology,” she says. “The scope and potential is significant, but the question is which market segments will prove to be a real home for it?

“Our sense at the moment is that it will evolve into a suite of specialist processes capable of manufacturing particular components, and those of course could end up anywhere in our building stock.”

Skanska’s Stacey agrees: “I may be wrong but I don’t see the business case for 3D printing whole buildings. I would be surprised if they become more economically viable than traditional contracted houses anytime soon.”

So we may not see Barratt Homes pumping out 3D-printed houses in the near future, but 3D-printed elements look set to be seen on site very soon.

“Contractors should be keeping an eye on it, for sure,” concludes Glass. “While it’s really a manufacturing process in itself, 3D printing will become part of construction in years to come and contractors should start thinking about how it will affect the way information is handled – all the way from design, and manufacture, to construction. Laggards could easily lose out, particularly if they’ve not engaged with BIM to date.”